Artist Vicente Saavedra’s path was once conventional, until art set him free.

By Isabella Aranda Garcia

Photography by Justin Negard

The walls of Peekskill artist Vicente Saavedra’s Dobbs Ferry studio are lined with unfinished canvases, paint-splattered sketchbooks and scattered stacks of well-loved brushes. Classical or jazz music hums in the background. The space is an in-between, neither pristine nor chaotic, where discipline meets creativity, reflecting the journey Saavedra took to get here.

The former financial analyst-turned-artist-and-teacher took a leap of faith after the 2008 crash, leaving his well-paying job for the life of an artist. Art has always been a part of Saavedra’s life; he spent his formative years in Venezuela, where his artistic foundation quietly sprouted. Without formal art training, he fed his desire to create by copying images from schoolbooks and immersing himself in observation and detail, unknowingly laying the groundwork for lifelong artistic exploration.

- Watercolor and ink of statue.

- Watercolor and ink of street.

- Watercolor and ink of buildings.

Becoming a student

Saavedra was born in California, but his earliest memories belong to Venezuela. His family relocated there when he was just two, immersing him in the language, culture and sounds of his new home. Creativity wasn’t something he had to search for; it was part of the household atmosphere. Surrounded by music and art, expressing creativity felt natural. “I was always drawing, painting and playing music,” Saavedra recalls. “It was kind of natural for my family. My uncles were all musicians and visual artists. Music and art were always present in my life.”

Saavedra did not receive any formal art training growing up. “But I was always drawing on my own, just copying things I saw.” In school, while flipping through his history books, he would see paintings by Venezuelan artist Arturo Michelena. “I remember this famous painting, Miranda en la Carraca; it’s a portrait of General Miranda when the Spanish army captured him. For me, those images were really powerful.” Michelena’s 19th-century academic art, which combined elements of romanticism and realism, motivated young Saavedra to work on his artistic skills. “His style was challenging to replicate, but I was motivated to paint like that. So, as a child, I started doing realistic work.”

At 18, his life pivoted. Saavedra moved back to the U.S., a country where he held citizenship but felt like a stranger. “My dad and I sold everything,” he explains. “I hated the whole thing. I left friends, girlfriends, everything. And I had to do this because I was an American citizen.” He spoke little English and was suddenly immersed in a new world, relearning the language at night while working and studying international relations and French at NYU by day. “So I was an 18-year-old kid with immense pressure.”

That period, though difficult, became foundational. During this challenging time, Saavedra found motivation to move forward by working towards a goal: mastering painting forms in a realistic manner. That desire became his light at the end of the tunnel. “I just sort of trained myself—when I see a light, I want it. It’s survival.”

Eventually, Saavedra, who double majored in French and political science, took his artistic ambitions across the Atlantic to France through a study abroad program. Outside of being a student, living in France gave him a sense of pause to reflect on his future. “When I was in France, it gave me time to think, ‘What am I doing?’” he says. That question followed him after the program ended and he moved back to the States. But Saavedra dreamed of earning a master’s degree, so he completed his undergraduate studies. “I focused on it, but not with that desire. I didn’t want to regret not finishing it.” He then earned a master’s degree in French social science and entered the world of finance, where he spent 15 years.

Painting, however, remained a quiet constant in his life. After long days in a job that never ignited his passion, he would return home, work on projects and take art classes. “I was painting at night… but after the crash, I said, ‘This is it.’” For Saavedra, the 2008 financial crisis was the wake-up call he needed to fully commit to art.

Saavedra next to his self portrait.

Becoming a teacher

That leap of faith began in a two-car garage in Irvington, which he transformed into a home studio. There, he started teaching neighborhood kids the fundamentals—light, shadow, proportion, color—laying the groundwork for what would become the Art Academy of Westchester in Dobbs Ferry, which opened in 2010. After a couple of years, he began teaching at The Masters School, where he still instructs students in seventh and eighth grade.

His approach is rooted in structure and patience. “If they know the structure, they can fly,” he says. “I love when they get it, when something clicks and they realize they can do this,” he explains. “It’s not about talent; it’s about patience, discipline and the approach.” His philosophy goes beyond students’ grades. For Saavedra, it’s about the ambition to create. “It’s the C student that creates the business,” Saavedra says. “Often, they are the ones who want to make something.”

At the Art Academy of Westchester, he welcomes students of all ages and skill levels, many of whom have gone on to art schools and creative careers. But for Saavedra, it’s not about the accolades. It’s about giving others the tools to find their visual voice, just as he once did. “I had people who gave me their time, who taught me. So, I want to pass that on. It’s a cycle.”

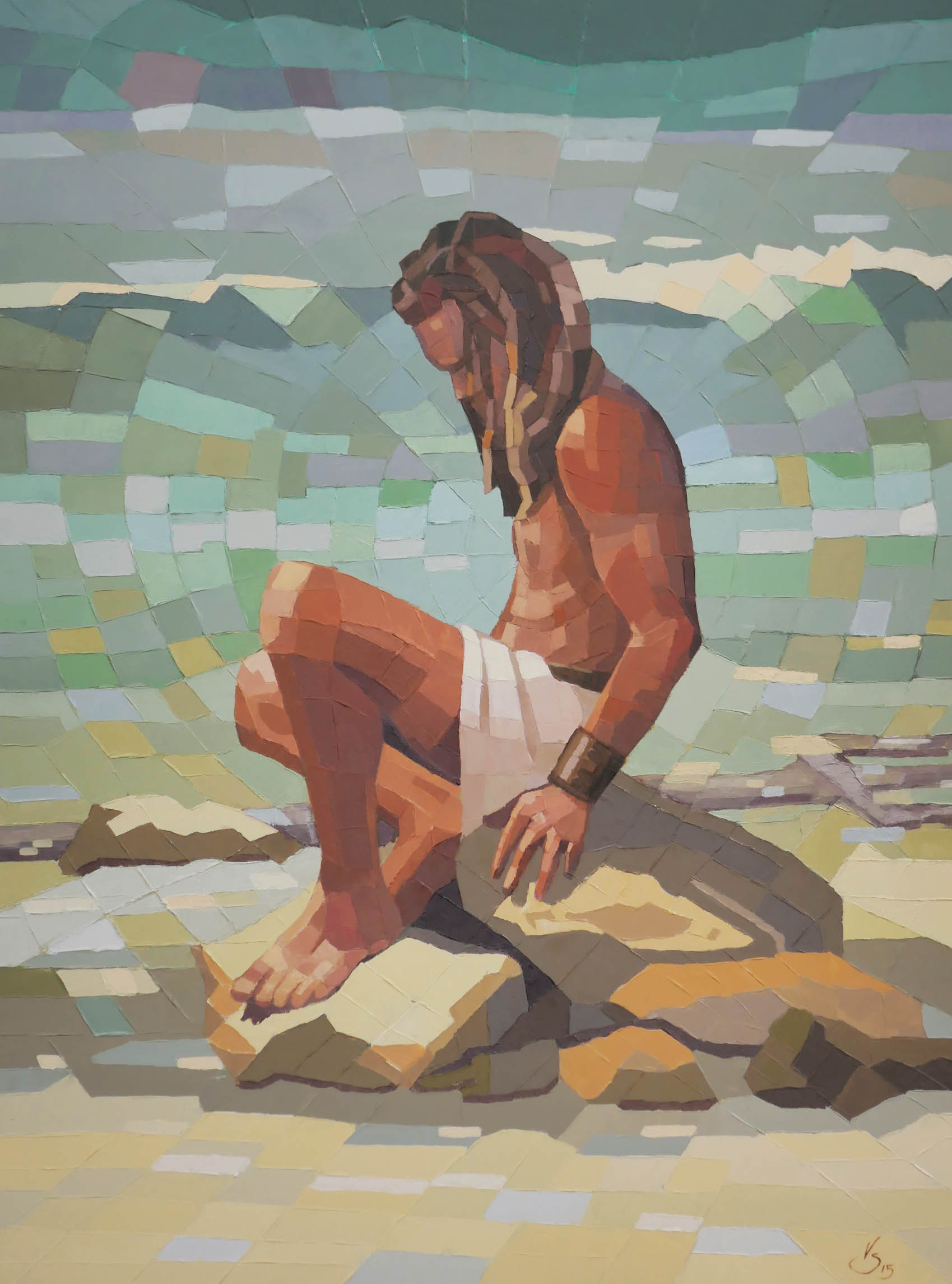

- “Poseidon” 36 x 48 inches, oil on canvas.

- “Resilience” 30 x 40 inches, oil on canvas.

Becoming an artist

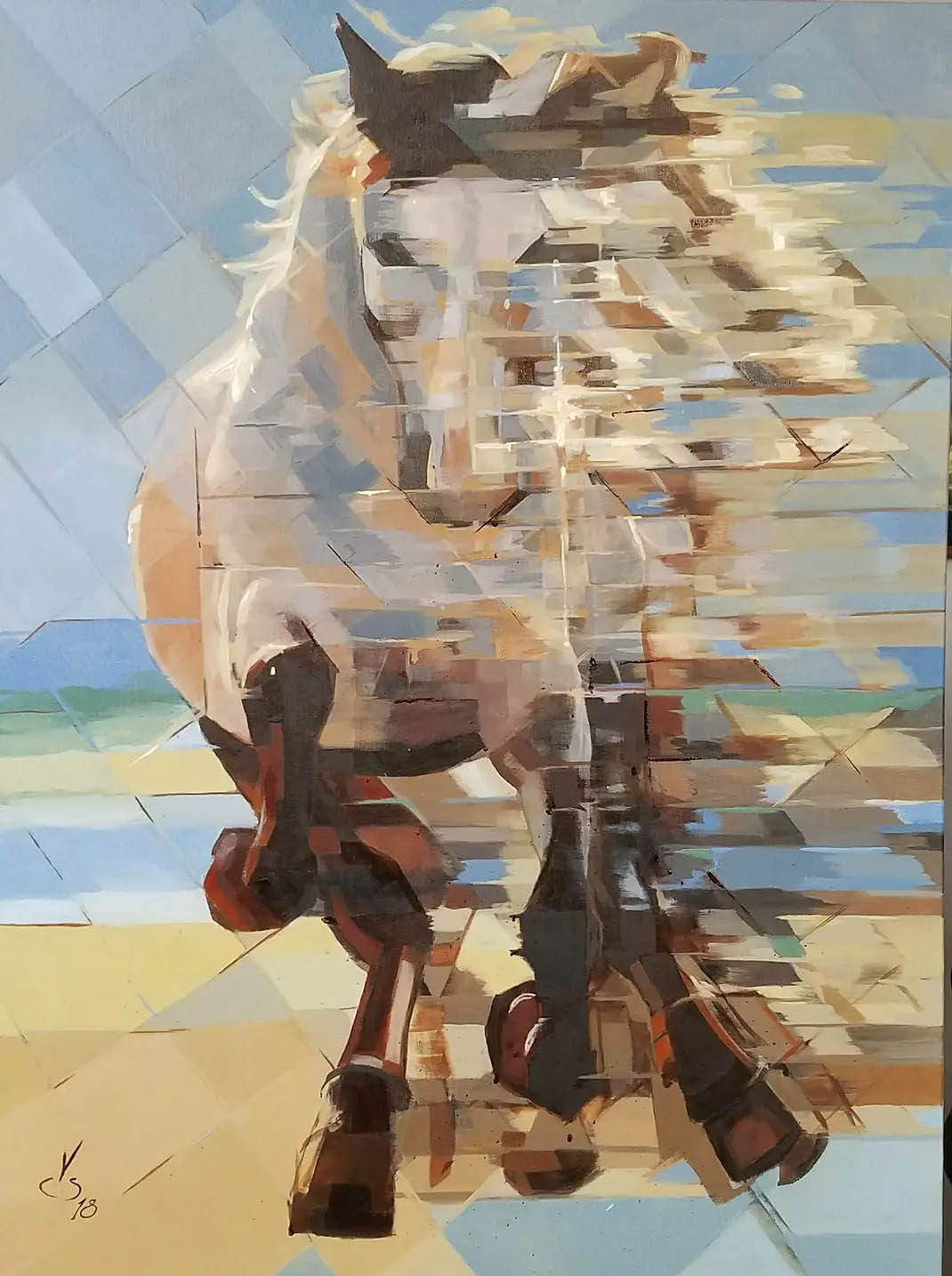

Saavedra’s artwork features classical techniques with a contemporary lens. Many of his paintings explore the human form, detailing human anatomy in different shapes and poses. Saavedra believes learning anatomy is essential if an artist wants to understand how to paint the human figure. He will often blend the realism of the main figure with a dynamic, modern background, frequently a mosaic. His figures often exist in states of motion or reflection, caught between light and shadow, and shaped by a blend of geometry and organic forms. “With that, I create movement.” And in Saavedra’s work, the devil is in the details. His paintings often contain layered narratives—hidden details, subtle symbols and visual puzzles that reward the attentive viewer. “There’s always a story behind the image,” he explains. Referring to his oil painting Allegory of Painting (Pegasus), he says, “It’s not just a horse; it’s mythology, history and mystery all in one.”

Another work features Poseidon sitting on a rock, gazing out into the ocean. At first glance, Poseidon looks like any man lost in thought, with no obvious sign that he could be a god. “It’s a distressed Poseidon,” Saavedra explains. “All the oceans are contaminated with garbage islands of plastic. He’s done with his job of being the god Poseidon.” Only a careful eye will notice the hidden trident in the background. “I put a lot of hidden things to help people look instead of just glance. If they keep looking, they might find it interesting. That’s my hope.”

One of Saavedra’s most personal works is his self-portrait, though it didn’t begin that way. What started as a loosely formed image, featuring a clear baseball cap and dark hair, sat unfinished for years. “I spent many years working on that painting before I knew what to do with it,” he explains. He’d return to it occasionally, adjusting small details like the hair, but without a clear sense of purpose. Over time, the portrait evolved into something more meaningful—a visual narrative of self-discovery. “Finally I knew what to do with this thing, and I turned it into that story,” he says. The finished piece of his self-portrait became not just a likeness but a quiet record of transformation—evidence of how reflection, patience and personal growth can shape a canvas as much as a life.

His latest unfinished work is a large-scale canvas (measuring 8’ x 9’) of Artemis and her hunting group. “She was very cruel but also very generous. She was a hunter but also a protector of nature.” The painting captures that contrast—moments of calm paired with the underlying energy of the hunt.

Saavedra has a fascination with mythology, recently focusing his interest on Bacchus, the Roman name for Dionysus, the god of wine, fertility and theater. But for Saavedra, Bacchus is more than a symbol of revelry. “People forget Bacchus was also a teacher,” he says. “He wasn’t just about the party; he taught people to live, to enjoy, to feel. That’s what art does, too.” For Saavedra, Bacchus is a metaphor for creative release—messy, emotional, even overwhelming, but ultimately transformative. “I am thinking about painting Bacchus next because he’s about being alive,” he says. “Being overwhelmed, inspired, ruined and remade—that’s art.

“60 Miles” 4 x 3 feet, oil on canvas.

This article was published in the September/October 2025 edition of Connect to Northern Westchester.