Writing by Gia Miller

Photography by Justin Negard

Alex Gorman and Rocco Cambareri sat down perpendicular to each other at a long wooden table. It was time for their weekly songwriting class with Brian Laidlaw, who was at the other end.

“I have been thinking about those people who are forces of nature,” said Gorman.

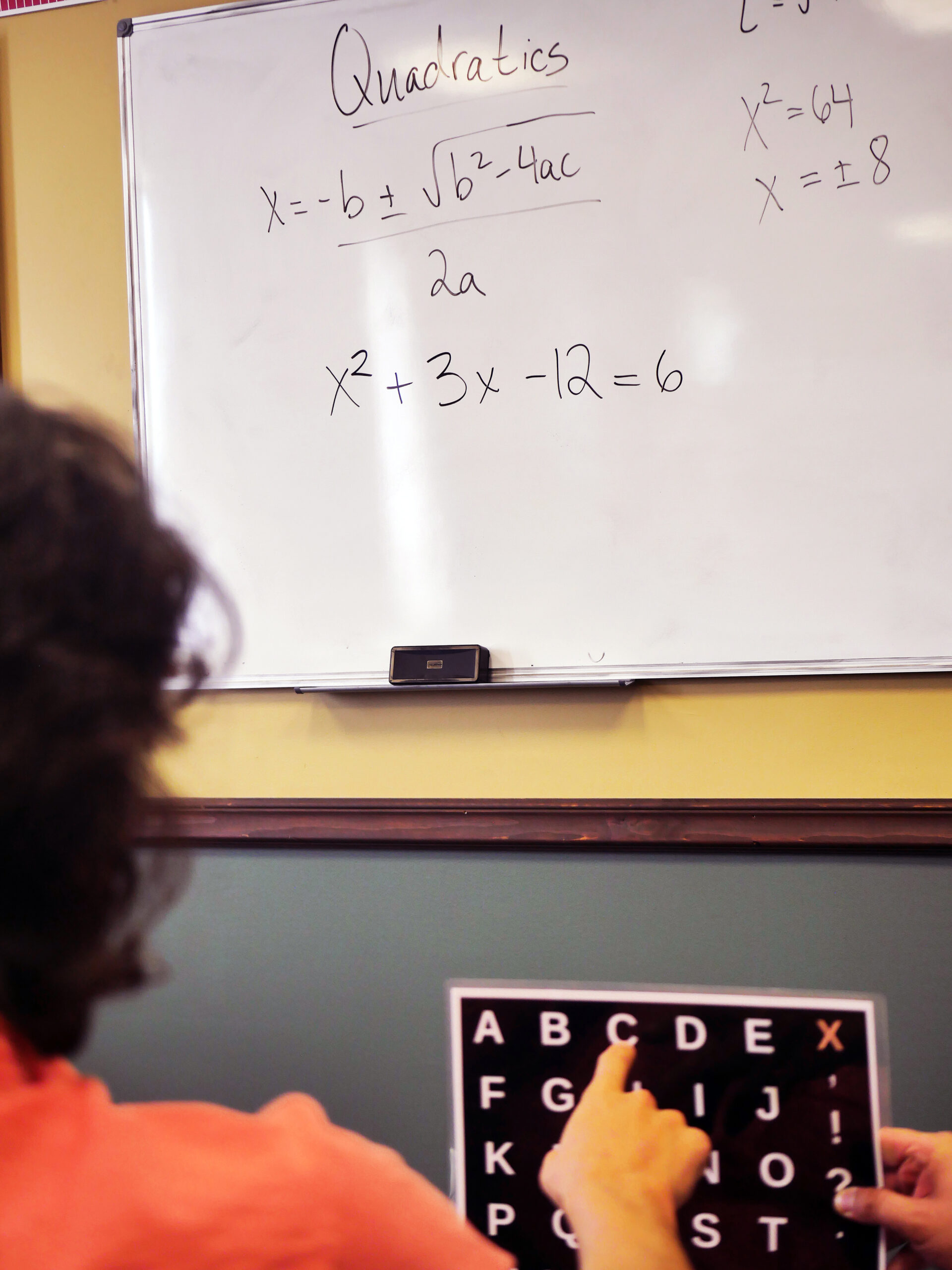

Laidlaw, who was teaching the class via Zoom, turned his attention to Cambareri and asked him what he thought of the idea. Cambareri began pointing to letters to spell out his answer.

“FORCES OF NATURE CAN ONLY MEAN JUDY,” Cambareri wrote. “SHE IS LOVE ITSELF, AND NOTHING CAN STOP HER.”

Then, they began working on the song, each student taking a turn to write two lines. Cambareri went first, beginning the song with “So many people live small lives, leaving no footprints behind them.”

Laidlaw explained there aren’t a lot of words that rhyme with “them,” so ending the second verse with “behind” would make it easier for Gorman. They all agreed, and it was then Gorman’s turn to compose two versus, ending with a word that rhymed with “behind.”

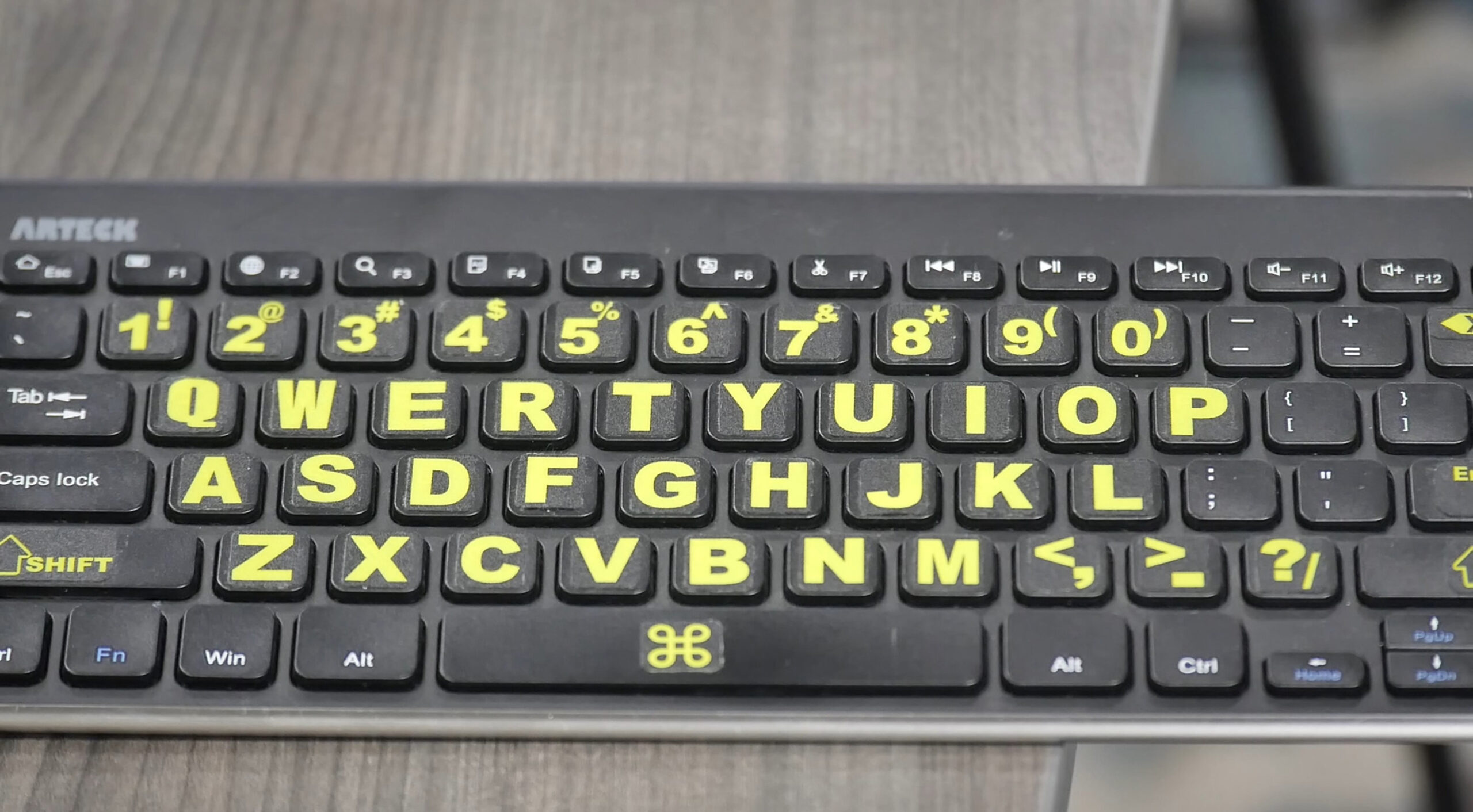

Gorman asked for a minute to think. Soon, he began to type his verses on a keyboard, touching each key with one finger. Four and a half minutes later, the next two lines were complete: “And while they see the evils of the world; They act as if they’re blind.”

The remainder of the class continued in the same fashion, each student writing two verses at a time. The back-and-forth collaborative nature was one of friends who truly knew, trusted and respected each other. About thirty minutes later, they’d written three verses:

So many people live small lives

Leaving no footprints behind

And while they see the evils of the world

They act as if they’re blind

Perhaps they don’t care enough

Or believe someone else will do it

But then there are those who see and do

Who try and never quit

There are people who change the world

They are the people who shape and act

They clearly see what the world should be

They live to have impact

As they wrote, they thought about Judy Chinitz, who Cambareri mentioned at the beginning of the lesson. Chinitz, who is Gorman’s mother, is the founder/director of Mouth to Hand (M2H) Learning Center in Mount Kisco. A special education teacher and certified Spelling to Communicate (S2C) practitioner, Chinitz has spent the past three years changing the lives of approximately 60 people who, until they met her, had no way to communicate with the outside world.

Chinitz’s students cannot speak with their mouths, and due to severe dyspraxia (a developmental condition that affects movement and coordination), they cannot use sign language. They were all diagnosed with autism and believed to have a very low IQ. But every one of her students have proved their doctors, teachers, therapists and even family members wrong.

In the beginning

To understand how Gorman, Cambareri and their peers finally learned how to communicate and why it is worthy of a story (and much more), the history is important.

Gorman was about 12 months old when he and his family moved from Manhattan to London. He was hitting all his developmental milestones and spoke words like “cookie” and “cracker.” About three months after arriving, he and his mom caught a virus. Chinitz likened her symptoms to a 48-hour stomach bug, but Gorman’s symptoms were much worse; they changed everything.

“For him, it lasted about three weeks,” Chinitz remembers. “Afterwards, there was a distinct change in his whole personality. His skills began to regress, and I knew that there was something very, very wrong. I brought him to our GP in London, but he shrugged it off as a reaction to new germs in a new country. I then took him for a hearing test, which consisted of two women standing behind him and yelling, ‘Alex!’ They diagnosed him with mid-range hearing loss, but I knew that wasn’t the problem.”

When he was about two years old, Chinitz brought Gorman back to New York to see a developmental pediatrician and neurologist. He was diagnosed with autism – she was shocked. When she studied special education in graduate school, they were not taught that autism could be regressive. In fact, she says it took another 10 years after his diagnosis for regressive autism to be acknowledged by the medical profession.

“When I learned he had autism, I felt such utter devastation that I couldn’t think too logically,” she remembers.

It is one of Gorman’s earliest memories.

“I remember being diagnosed,” he says. “I remember my mom crying and the doctor saying, ‘autism.’”

Raising Gorman was “incredibly difficult.” Chinitz and Gorman never returned to London after the diagnosis, and she sprang into action. Chinitz quickly arranged therapy sessions (“I had him in therapy 40 hours a week,” she says), studied the latest research and regularly took him to the doctor because, in addition to autism, Gorman has “always had terrible immune deficiencies and dysregulation.”

At age two, he was so sick that he was bedridden for eight to 12 weeks.

“We obviously don’t know exactly what caused him to regress, but that’s probably a large part of what happened to him,” she says. “After the autism diagnosis, he continuously became physically sicker and sicker, and he mentally regressed more and more. Finally, just after his third birthday, a pediatrician sent us to an immunologist who immediately diagnosed him with an immune deficiency and started treatment right away.”

According to Chinitz, Gorman’s story (his diagnosis and other health struggles) is similar to the stories she’s been told by her students’ parents. And while each parent handles it their own way, the outcome is mainly the same.

“Every one of them was diagnosed with pervasive developmental disorder when they were between two and three years old; they don’t call it autism until you’re five,” Chinitz explains. “But basically, they’re diagnosed with nonspeaking autism or low-functioning autism. Every one of them was put into a program for the cognitively disabled where there is a prescriptive educational methodology. Every one of them failed to make any kind of significant progress, which, experts say, only confirms how low functioning they are. And then, at 21, they take them out of school and put them in a daycare program where they watch TV, shred paper, do simple clerical work, sort recycling and/or stare out the window. And that will be how they live the rest of their lives.”

A letterboard for spellers.

A life-changing decision

While raising Gorman, Chinitz would often speak with a close friend who lived in New Jersey named Ginnie Breen. Breen’s daughter, Elizabeth Bonker, was also diagnosed with nonspeaking autism, and she was just a few years younger than Gorman.

When Bonker was five years old, Breen took her down to Texas where Bonker learned how to communicate via something called Rapid Prompting Method (RPM), which teaches people how to communicate by pointing to letters on a letterboard (a flat board with letters, numbers and symbols).

Once Bonker could communicate and mastered typing, her mother fought for her to be placed in mainstream classes at her local public school. She began studying in a general education classroom in first grade.

When she was 11 years old, Bonker published a book of her poetry and stories that describes her life and journey titled “I Am in Here: The Journey of a Child with Autism Who Cannot Speak but Finds Her Voice,” and she began her advocacy work.

Bonker graduated high school and attended the honors program at Rollins College. In 2022 she was one of five students who earned the title of valedictorian. The other four instantly and unanimously voted for Bonker to give the speech – it went viral.

Today, Bonker, who is 25 years old, is in talks with legislators in Washington D.C. to amend the Autism CARES Act to include access to communication for the estimated 40 percent of people with autism who are nonspeaking.

Breen always believed Gorman could learn to communicate, so Chinitz says Breen regularly “nagged” her about it. But Chinitz couldn’t afford the trip to Texas, and she didn’t really understand what Breen was trying to tell her.

“I thought Elizabeth was an anomaly,” she explains. “In my work, I had personally witnessed a kid be cured of autism, but they are anomalies. I didn’t think it applied to my child. I didn’t understand that this nonspeaking population, as a whole, struggled with motor issues because nobody ever really talks about the motor issues in this population. But we all noticed it. We all knew they couldn’t motor plan. We all knew they had bizarre gaits. We knew they couldn’t write. But everybody kept presenting it as a cognitive thing, not a motor thing.”

Eventually, Breen learned about a speech therapist in Virginia named Elizabeth Vosseller who had learned RPM and eventually developed S2C, which is similar to RPM but is based on science. Vosseller’s reason for developing this method was her belief that if it’s science-based, then schools would begin teaching it (more on that later).

Eventually, Breen convinced Chinitz to visit Vosseller’s Growing Kids Therapy Center.

On July 1, 2019, when Gorman was 25 ½ years old, Chinitz and Gorman woke up in a hotel room. As Chinitz got dressed that morning, she turned on “Thomas the Tank Engine” for Gorman – it was a show she knew he loved. That was one of the last times Chinitz ever placed Gorman in front of “Thomas the Tank Engine” or the Disney princess movies she knew he also loved. Because, as she eventually learned, she didn’t really know her son at all. That path to discovery began later that day when they met Vosseller for the first time.

Over the next two days, Vosseller began teaching Gorman “the motor skill of holding a pencil and trying to poke it through large, stenciled letters” (which dyspraxia makes challenging). Chinitz was told to observe so she could learn how to help him herself.

“She worked with Alex for two one-hour sessions on day one, and another hour the next morning,” Chinitz remembers. “Then, on the second afternoon, she had me sit down with Alex for about 30 minutes so she could show me what to do.”

When they returned home, Chinitz figured the rest out on her own and continued to work with her son, despite her family members telling her that she was wasting her time. No one, including Chinitz, believed Gorman had the intelligence to communicate, but she persevered anyway.

“What did I have to lose?”

(L-R) Judy Chinitz, Elizabeth Bonker and Ginnie Breen working on instructional videos for Communication for ALL (C4A), a non-profit with the mission to give all nonspeakers with autism access to communication and education. C4A Academy will launch this fall as a program of internet-based instructional videos that teach typing to nonspeakers anywhere, free of charge.

Joy and guilt

“I used to tell people that even if the hand of God came down and touched Alex while he was sleeping, and he woke up the next morning and didn’t have autism, I would still have to teach him one plus one,” Chinitz says.

On October 5, 2019, Chinitz learned that she was very, very wrong. That was the day it all clicked for Gorman. That was the day their lives changed.

“One day, he started talking to me,” she remembers. “And very rapidly, I started to recognize extreme intelligence. It was so earth-shattering for me because I had to completely revamp everything that I thought to be my reality. My reality wasn’t actually reality. It was a shock. And it was a shock over and over and over.”

Gorman knew how to read. Gorman could calculate square roots in his head. Gorman spoke French!

“That morning, I was literally putting little men in boats and asking, ‘If four men are in a boat, and one more man gets in, how many men are in the boat,’” she remembers. “And then, he suddenly poked the five! I started screaming because he finally had the motor skill. Then I realized he understood numbers. So, I said, ‘If two men get out of the boat, how many are left?’ And he tapped three.”

“So, I came flying down the stairs,” she continues, “and I find my father in the kitchen. I said, ‘Dad, look at this. I think Alex knows addition and subtraction.’ I was doing single digits with him, but then I started to wonder if he knew anything with double digits. Then, I started with multiplication. Every single question I asked him, he answered correctly.”

“It started getting crazier and crazier,” she remembers. “At some point, I asked him something like the square root of 144, and he instantly tapped 12. So, I kept upping the level of questions to see where it was going to stop, and it just never did. Eventually, I asked something like, ‘100 minus X equals 50; what is X?’ And he tapped 50. Then I asked him if he knew what ‘X’ was called, and he spelled ‘variable.’ That was the point at which I stopped. In one day, I’d learned that he knew cubes and square roots, and he knew what exponents were. I was thrilled, but that feeling was also mixed with this horrible sense of almost grief. Because, here I am, for 25 years, making this poor kid listen to me talk about putting men in boats, and he has this savant skill called lightning calculation where he can do complicated math in his head, instantly.”

Gorman was self-taught. He figured out how to read as a toddler, and as he got older, he’d sneak into his younger brother’s room to read his textbooks. But he had to do it quickly because he knew that if he got caught, he’d get yelled at for messing up his brother’s things. Luckily for Gorman, he also has an eidetic (photographic) memory.

Over the years, Gorman learned everything he could, but he was trapped. Without the ability to speak, he couldn’t share his thoughts with anyone. It was his faith in his mom that kept him going.

“I knew that one day, she’d figure it out,” he explains.

And while there was tremendous joy in finally meeting and communicating with her son, Chinitz says there was also tremendous guilt.

“One day, we were sitting next to each other on the couch, and he overheard me tell somebody that I had known about spelling for about 15 years because of my friend Ginnie,” Chinitz remembers. “Then Alex turned to me and said, ‘So I could have been talking since I was 12?’ And I lost it. I don’t think I stopped crying for five hours. It was so overwhelming; I had such guilt.”

“There are just no words for it,” she continues. “I realized what I had done to him – not just being unable to talk, but a lifetime in schools and programs for the cognitively impaired, sitting in a daycare program doing nothing, hour after hour, all day every day. I said to him, ‘I can never make it up to you; there’s nothing I can do. But I’m going to try as best as I can. Even though I can’t, I’m going to try to fix this for you. He said he knew I didn’t know, and he wasn’t angry; he always believed that I would figure it out.”

Planting the first seed

As Gorman became more comfortable with the letterboard and began studying for his GED, Chinitz decided to start “a little tutoring business” in her basement to help others communicate. She opened her doors on May 17, 2020, wearing two masks. She had one student.

“I thought I would just have five or six students and earn some extra income,” says Chinitz. “I really, truly had no idea. I had no inkling of what it was going to turn into.”

By month two, she had two students. By month three, she had four, and by the fall, she had seven. Then, in April 2021, the book “Underestimated: An Autism Miracle” was released – it’s about a boy just like Gorman who learned how to communicate by spelling. Her “little tutoring business” exploded.

Chinitz began to understand that Gorman was not another anomaly – he was representative of a population of people diagnosed with nonspeaking autism. Their inability to speak, Chinitz believes, is due to severe dyspraxia. But, because most people with dyspraxia can speak, Chinitz says that clinicians/experts don’t associate the inability to speak with dyspraxia or any sort of motor planning issue. Instead, they believe it’s due to low intelligence.

“Because Alex cannot speak with his mouth, they knew he was cognitively disabled,” she explains. “They believed he couldn’t communicate because he had a cognitive issue, not a motor issue. Everything comes down to verbal speech.”

A speller using a letterboard.

Rapid growth

In December 2021, Chinitz had outgrown her basement and opened Mouth to Hand (M2H) Learning Center in Mount Kisco. One year after that, she moved to a larger space, also in Mount Kisco, with six classrooms and a lobby that doubles as a learning space (it’s where the music class is held, among other things). This space has plenty of room to grow.

“It was a big leap of faith for me because I’ve been a single mom since 2005, so I’m not really in a position to take financial risks,” says Chinitz. “But I decided to sign the lease and hope and pray.”

“And, of course, it turned out great,” she continues. “We all joke that if I build it, they will come. And that’s what happened. As soon as I build something, it fills. It’s all worked out as best as it possibly could have.”

Chinitz now has six employees, half of them part-time, who help her teach, develop community classes, and manage the administration and bookkeeping. Plus, a few of her family members volunteer their time, like her father, who’s known as Grandpa Wally – he’s a retired rocket scientist who teaches music appreciation and is beloved by everyone there.

Chinitz says that as long as they’re old enough to sit relatively still and learn, she can teach a nonspeaking person diagnosed with autism how to communicate. This is because, she says, they’re not actually cognitively impaired. In fact, most of them, like Gorman, taught themselves how to read when they were two or three years old – they’re highly intelligent, and some are even brilliant. The first time she meets a new student, Chinitz tells them, “I know you’re intelligent, and you’re going to talk to me.”

She says many of her students have told her they’ve lived the majority of their life in a dream-like state, and one of their first clear memories is meeting her for the first time. Chinitz thinks this might be because their life up until that point has been so full of frustration and disappointment that it’s how their brain copes with the trauma.

“Autism is a garbage can diagnosis,” she says. “Everybody’s labeled autistic, but in actuality, autism is a deficit in language and social skills. People with autism don’t understand that people think differently than them. They also have repetitive behaviors and limited interests.”

Chinitz is very clear about the fact that she isn’t a diagnostician, but in her opinion, her students do not have autism. She imagines they have “a completely separate disorder” that impacts their impulse control, anxiety and OCD, among other things. She says they are “completely aware of the emotions of the people around them,” are complex and compassionate, ponder complicated ethical and societal problems, and they have a wide variety of interests – it doesn’t fit the autism diagnosis.

At M2H, once they’ve learned how to communicate, they study math and science, play games together, write poetry, compose lyrics, crack jokes (they’re really funny), tease each other and cheer each other on.

“I have found my people,” she says. “I tell them daily that I’d rather be with them than pretty much anybody else on this planet. They’re ethically, morally and intellectually superior human beings. They’re the kindest, most compassionate, most empathetic, most brilliant people I’ve ever met.”

Judy Chinitz, Anthony Piccolino and Rocco Camberi in song writing class.

Hans the horse

Not everyone believes what Chinitz does is real. Holding the letterboard is a trained skill, and not everyone can do it. Part of the reason, she believes, is because her students are highly empathic – they’re incredibly sensitive to others’ feelings and moods. They need someone to encourage them and cheer them on.

“When you go to a Yankees game, you cheer for the Yankees, and you boo when their opponent comes up to bat,” says Chinitz. “What you’re doing is creating a positive atmosphere for the Yankees and giving them a home field advantage. Scientific studies have shown that people’s motor skills improve when you’re cheering for them. That’s why sports teams do better at home, and that’s what I’m doing when I hold the letterboard. I’m cheering them on. I’m giving them that home team advantage.”

“I’m also an effective communication partner, because I’m highly regulated,” she continues. “I’m very, very calm. These guys are empaths, and they know that I’m calm. They know that I don’t react to their self-stimulating behaviors, and it makes them better able to regulate their own bodies.”

But that explanation won’t sway everyone. For example, when the director of special education from a local school district came to observe a student in his district, he accused Chinitz of putting words in her student’s mouth.

“He actually said to me that my students are basically Hans the Horse,” she says. “Hans the Horse is a story from the 1800s, about a guy who claimed he had taught his horse, Hans, how to count and do math. Hans would neigh and stomp his hoof, and everyone thought the horse was brilliant. But it was later proven that Hans was just following signals from his trainer. So basically, this superintendent was saying that he’s the only one who is intelligent enough to recognize that I am telling my students what to say, and all my students are just like Hans the Horse.”

“So, I explained to him that there are 32 characters on this letterboard alone, and every time my students pick a correct letter, there is a one in 32 chance of them getting it right,” she continues. “All I’m doing is holding the letterboard. I’m not moving a muscle. So, if my student uses 500 letters to correctly answer a question on a test, but he’s actually incapable of having his own thoughts, then he has a greater chance of being hit by lightning three times in the same place than he does of spelling out the correct answer. It’s not mathematically possible. I must be some kind of miracle worker if I am telling him what to say without moving a muscle, and he’s getting it right every single time. There’s no way on earth that I could do that. It can’t happen. It’s just not possible.”

However, some parents believe that money, not disbelief, is the main reason schools refuse to recognize or teach this form of communication. They say that if schools accepted S2C, then the district would be required to train the staff and hire additional communication partners to work with the students. Plus, that would demonstrate that they’ve failed to teach students who are, in fact, very teachable. And that could open them up to hundreds of lawsuits.

So instead, schools tell parents that children who can spell to communicate will remain in the self-contained classroom that’s designated for the most severely cognitively impaired students. They’ll spend their days completing mundane tasks like filling a jar with buttons or adding “1 + 1” on a calculator over and over again. It’s mind-numbing and unacceptable, and many parents feel they’re left with no choice but to homeschool their kids.

“They do not understand what they are doing to us,” says Gorman. “They believe we are cognitively impaired, and they cannot see beyond it.”

A daytime haven

Chinitz says that she has taught several elementary school students and teens how to communicate, but a lot of her students are in their early 20s because “that’s when they’re about to be dumped out of the school system and parents realize that there’s nothing out there for them – they’ll be stuck in a daycare program forever.”

Parents are looking for alternatives, and they’ll drive from as far away as Massachusetts and Pennsylvania to bring their children to M2H at least once a week. Once their child has learned to communicate on a letterboard, they start taking classes.

“I had this dream of creating a community where my son could be seen for who he was, and I did that,” says Chinitz. “My new dream is to help all my students achieve their dreams.”

At M2H, students can take math, science, advanced science with lab, literature, history, current events & society, writing, poetry, music appreciation, movies: history and analysis, and, of course, song writing. Many students are studying for their GED and want to attend college.

Gorman earned his GED two years ago, once the testing centers reopened after the pandemic. But to receive the accommodations he needed, Gorman first needed a neuropsychological evaluation to prove he was capable, intellectually, of taking the test. That’s when they learned his IQ is over 150. He received some of the accommodations he needed and took the test over several days. He, of course, passed.

“That was actually a really interesting experience for me as well,” says Chinitz. “Because the women who were the proctors were not believers when we walked in. When he wrote his 2,500-word essay on recycling, one woman watched us carefully to make sure we were not cheating. When he was done, they said, ‘That was the most inspiring thing I’ve ever seen in my life.’ Then they called when he passed because they were so excited. A few months later, they called again because they wanted to know what he was going to do. Was he going to go to college? They did a complete 180.”

Chinitz says that one of the first things Gorman said to her when he could finally communicate was, “Can I go to college?” And this fall, he will.

“I will get my degree at Purchase and write my Tony-award-winning play,” he says.

What will his play be about?

“The stupidity of mankind: the condescension, the cruelty, the complete lack of imaginative thinking – so, a hilarious comedy,” he says.

To clarify, although the students at M2H have learned how to communicate, they are still trapped in the same bodies – bodies that Chinitz says have “betrayed them.” And so, people stare; they whisper, sometimes loudly; they point. It’s hard to endure.

“Their bodies are not functioning, but their spirits and minds are normal,” Chinitz explains. “It breaks my heart because they all know what they look like to other people. They all know their bodies are doing weird things, but they can’t stop it. It means so much to them to have people treat them with respect and to look at the inside, not the outside. And honestly, what does anybody really want? We all want to be known for who we really are and loved for it, right?”

“People are not at fault for not knowing,” Gorman adds. “But they are at fault for knowing and not changing what they do.”

Chinitz says she’s trying to give her students opportunities to “be and act and do things as normal as they possibly can.” She has given them a life, friends and an opportunity to show the world who they truly are. She says she hopes to do the same for even more people because the alternative is too depressing.

“I’m heartbroken thinking about how many of us will never talk,” says Gorman. “They will die never having a single person know them. You cannot imagine the loneliness.”

Founders’ note: Telling this story and spending time with the M2H students has been an inspiring, life-changing experience for us. So, we’ve decided to dedicate a page of our magazine and website to the students at M2H.

In each issue, you can now read a poem, op-ed or other writing from a nonspeaking person who can finally communicate. Click here for our new section, Out Loud and a piece titled “Visions” by Paul Klein.

Riyad Twal, the math and science instructor, holding a letterboard for Edison Lema during math class.

This article was published in the September/October 2023 print edition of Katonah Connect.

Gia Miller is an award-winning journalist and the editor-in-chief/co-publisher of Connect to Northern Westchester. She has a magazine journalism degree (yes, that's a real thing) from the University of Georgia and has written for countless national publications, ranging from SELF to The Washington Post. Gia desperately wishes schools still taught grammar. Also, she wants everyone to know they can delete the word "that" from about 90% of their sentences, and there's no such thing as "first annual." When she's not running her media empire, Gia enjoys spending quality time with friends and family, laughing at her crazy dog and listening to a good podcast. She thanks multiple alarms, fermented grapes and her amazing husband for helping her get through each day. Her love languages are food and humor.