Writing and photography by Justin Negard

Images courtesy of Michael Bierut / Pentagram

You know Michael Bierut’s work. You’ve seen it, read it, held it, visited it, flown with it, cheered for it and possibly even voted for it. Bierut is a designer—a graphic designer, to be precise.

“If I say that I’m a designer, people sometimes get excited because they think I’m a fashion designer,” says Bierut, who lives in Tarrytown. “Characters in movies are fashion designers. It’s glamorous. Graphic designers have always been a little more confusing to people because graphic design isn’t a thing in and of itself. It’s really about words and pictures. It’s a means to an end. In fashion design, the dress is the end. Graphic designers are trying to communicate a message to someone, inform them, amuse them, change their mind about something. The endgame is the change of perception.”

For decades, Bierut has informed and amused the public, designing for the likes of MIT, the New York Jets, Saks Fifth Avenue and more. The red checkmark from Verizon? That’s his work. Hillary Clinton’s arrow from the 2016 presidential campaign? Him again. That large gray sign in front of The New York Times building? Also him. If you texted a colleague on Slack, read The Atlantic or paid for something with Mastercard lately, Bierut was behind the visual identity for all of them.

“The great thing about graphic design is that it is almost always about something else,” Bierut says. “Corporate law, professional football, art, politics. If I can’t get excited about whatever that something is, I really have trouble doing good work. To me, the conclusion is inescapable. The more things you’re interested in, the better your work will be.”

It’s fair to say that Bierut is interested in many things, and he has the résumé to prove it. Bierut has been honored by the American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA) and was named an Honorary Royal Designer for Industry, the United Kingdom’s most prestigious design award. He has published several books on design, and his work is in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. However, he doesn’t consider himself an artist.

“An artist is responsible only to him or herself,” says Bierut. “They don’t really require an external prompt in order to initiate their creative process. Designers need to be faced with some sort of problem to solve. They’re designing something that’ll be tested against a criterion other than, ‘Does this please me?’”

For Bierut, design is about solving things. He loves the challenge of design, the puzzle behind a problem. “I can’t design anything out of my head,” he says. “I really need someone to come to me and say, ‘We’re a department store, and we need a logo. It has to be big and it has to go here, here and here.’ The more they give me, the happier I am. It’s like opening the newspaper to a fresh crossword puzzle. I’d be frightened to face a blank slate every morning.”

For the better part of 30 years, most mornings have found Bierut riding the train to his office at Pentagram—an independently owned design studio in Manhattan of which he is one of 24 global partners. Bierut has worked alongside notable Pentagram partners such as Paula Scher, Luke Hayman and Abbott Miller, all of whom have developed the visual identities for a stunning number of businesses and organizations across the globe.

Outside the office, Bierut has also become something of a design ambassador—the Neil deGrasse Tyson for the graphically inclined. From books and movies to podcasts and lectures, he has spent much of his career speaking to the importance of graphic design in our society. Ask him, for example, about how a confusingly designed voting ballot in Palm Beach County may have accidentally swung the 2000 election to George W. Bush. “About a thousand people later claimed they accidentally voted for Pat Buchanan, but they meant to vote for Al Gore,” says Bierut. “And what happened next? The invasion of Afghanistan, the invasion of Iraq. Design counts.”

The Cincinnati kid

Michael Bierut’s first design memory was at the age of six. “My father pointed out a logo from our car window,” recalls Bierut. “He told me, ‘Look at the way they wrote the word CLARK. That’s really clever.’ It was for a forklift manufacturer, and the letter ‘L’ in ‘Clark’ was picking up the letter ‘A’ next to it. I was dumbstruck. It was like a magic trick, like a secret that only he and I knew.” Bierut did not grow up around design. He lived outside of Cleveland in what he calls “a post-World War II middle-class upbringing.”

“I didn’t know anyone who did anything creative for a living,” recalls Bierut. “Everyone around me seemed to do practical things like working as barbers or at the Ford plant. My dad was a salesman for printing presses, so I suppose we had a connection to the world of publishing—literally the manufacturing side of it. But still, he was able to bring home things from the world of print that I remember getting excited by.”

As he grew, Bierut developed an eye for art and design. Vinyl album covers had a particularly strong influence on his creative mindset, perhaps none more than ‘Revolver’ by The Beatles. “There are four names on that album that everyone knows,” says Bierut. “But there’s another name on there too: ‘Klaus Voormann.’ When I was a feverish young artist in Ohio, I knew I wasn’t John, Paul, George or Ringo, but this Klaus Voormann guy who designed the cover? I could be him.”

Bierut studied at the University of Cincinnati’s College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning, which required students to work half a year in the industry of their focus. For him, this meant real-world training while also learning to manage things like deadlines and revisions. “In school, you’d learn real design theory,” Bierut remembers. “Then you’d go work at an ad agency or a TV studio. I learned a lot of skills that no one would even recognize now. Things involving rubber cement and X-acto knives and estimating the size of typography by doing mathematical tables to figure out how much room you needed to set this many words in 18-point Helvetica. I know all that stuff. I always thought, ‘Thank god I’m going into graphic design because I never want to mess with computers.’”

- Hilary Clinton’s arrow sign by Bierut.

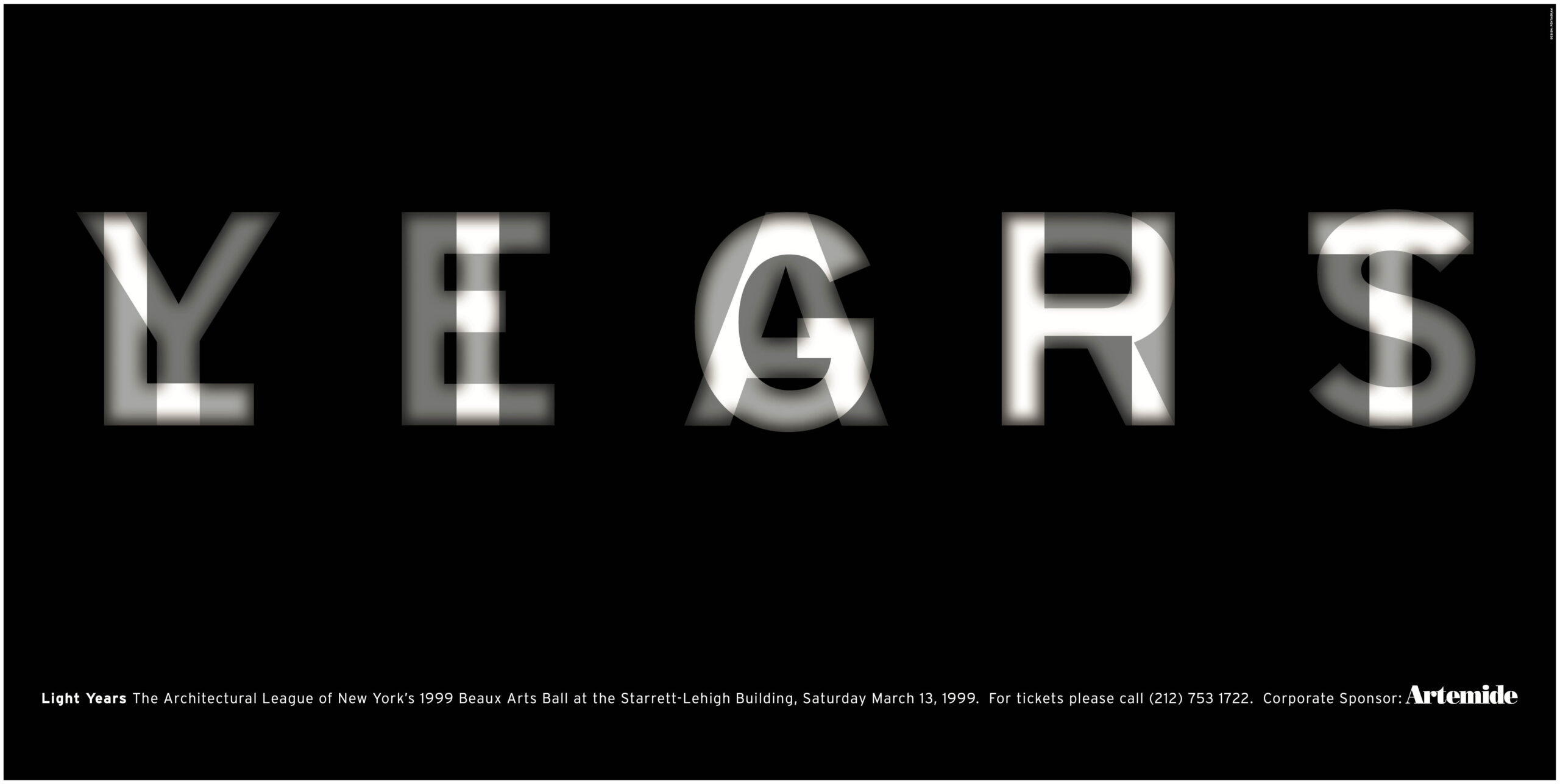

- The Architectural League of New York’s 1999 Beaux Arts Ball at the Starrett-Lehigh Building.

Learning the ropes

If there is a Yoda to Bierut’s Skywalker, it’s Massimo Vignelli. Born in Milan in 1931, Vignelli, a student of architecture and design, was a strong believer in the modernist Bauhaus movement. He moved to the United States in the 1960s and co-founded Unimark International, a design firm focused on corporate identities. In 1971, he founded Vignelli Associates with his wife, Lella Vignelli, an accomplished designer in her own right. The Vignellis designed furniture, dishware, books, logos and much more. One of Massimo’s notable works was designing the visual identity for the New York City subway system, which includes the black signage, multicolored circles and white Helvetica text that all New Yorkers have come to know.

The Vignellis gave Bierut his first professional foray into the world of design. These were deep waters for the new graduate to jump into, as he worked alongside the “titanic” Massimo and “impossibly glamorous” Lella, as Bierut describes them. “The Vignellis were incredibly worldly people,” he recalls. “Their ability to synthesize a client brief from a whole bunch of life experiences seemed foreign to me. It represented an unbridgeable gulf that I’d have to somehow cross. I remember thinking that I’m just going to fake it till I make it, nod during the day, and then go to the library at night and kind of figure out what the heck everyone was talking about.”

- The Slack app icon design by Bierut.

- The New York Times sign outside their building by Bierut.

- The Mastercard design by Bierut.

The Vignellis had what Bierut describes as a “very clear point of view,” a way of designing that was very strong but rigid. “I got it early on,” says Bierut. “This guy [Massimo] has a way of doing things, and my job is to figure out that way and deliver it accurately. I’m a good designer, but I’m an even better mimic.”

Despite the rigid structure of Vignelli Associates, Bierut searched for his own voice, often experimenting after hours on his own designs, with results that Bierut says were sometimes catastrophic. “There are rules for everything,” says Bierut. “Rules for how you write a sonnet or for how to make cacio e pepe. If you break them completely, it’s no longer a sonnet or that type of pasta dish. But if you bend the rules or morph them, you come up with something interesting.”

As time went on, Bierut continued to look for other ways of doing things. He sought out different voices and expanded his beliefs about what good design could be. “Massimo was a very charismatic guy who attracted a lot of New Testament-style disciples, but I was never one of those types of people,” says Bierut. “There are lots of really talented designers out there—the Paul Rands and Milton Glasers. If there was only one way to do it, are all those other designers doing it wrong?”

After 10 years, Bierut was hungry for more. Vignelli Associates allowed him to work on big projects, but eventually, that wasn’t enough. “I got to Vignelli when I was about 22,” recalls Bierut. “Now I was in my 30s, and I would either stay there forever and eventually inherit the firm, or I could do something else. I knew I would never figure out my own voice unless I was free of all of it.”

The Pentagram Experience

Bierut was on his own for the first time in his career. “I got used to having a nice big office around me,” says Bierut. “Now I had to find a little room, rent a telephone and get a Xerox machine? I didn’t have the stomach for it.” He stayed connected with the design community through organizations like the AIGA. It was there that he got to know a designer named Woody Pirtle, a partner in the New York City office of the design firm Pentagram. One night over dinner, Pirtle asked Bierut if he was interested in joining Pentagram as a partner. Bierut couldn’t believe it. “I was taken aback at first,” Bierut remembers. “I still felt like I was this young apprentice type of guy. It took me a while to say ‘Sure,’ although in terms of an agency model, it was all I really wanted.”

Pentagram is set up as a collective. There is no hierarchy like in a traditional design firm. Instead, decisions are made by consensus among the New York partners. When Bierut joined, he became the sixth. “The benefit of being in the group is the social aspect,” says Bierut. “The fact that you can turn around and ask someone how much they would charge for doing something or if they have heard of this person. You have a network at hand. It was exactly what I wanted.”

Joining Pentagram also put Bierut in a position of leadership. He was no longer under the guidance of the Vignellis. He now had to build his own client base and creative team. It took him a while to get comfortable delegating creative work, but it was something that he eventually relished. “I started hiring people who had a different skill set than me,” says Bierut. “Something happens in the handoff where they can add value that I couldn’t see. I’d send them a Reid Miles album cover and a picture of a building from Illinois, and I’d say, ‘It’s this sort of vibe.’ I’d get the most interesting results from it.”

Strategist-at-large

In 2024, Bierut decided it was time for another change; he semi-retired and transitioned into a consultant role at Pentagram. It was time to pass the torch and let new voices and perspectives take the lead.

Despite this change, there are still more problems for Bierut to solve. In 2026, the Obama Presidential Center will open to the public and include the enormous typographic inscription that Bierut designed for the top of the main building. When pressed if there are any remaining dream projects he would like to do, he responds with a firm and confident no. Bierut seems comfortable with his place in design history. “Graphic design is ephemeral,” he explains. “Some of the things I was most proud of got thrown out for something new. I can’t object to that because when I did it, I was replacing something that someone else did. So eventually everything I designed might be replaced.”

Only time will tell if Bierut is right. In the meantime, his work will continue to be seen on everything from shopping bags to stadiums, and he will continue to influence other designers, leaders and perhaps the next little kid discovering a magic trick of his own.

In 2026, the Obama Presidential Center will open to the public and include the enormous typographic inscription that Bierut designed for the top of the main building.

This article was published in the November/December 2025 edition of Connect to Northern Westchester.

Justin is an award-winning designer and photographer. He was the owner and creative director at Future Boy Design, producing work for clients such as National Parks Service, Vintage Cinemas, The Tarrytown Music Hall, and others. His work has appeared in Bloomberg TV, South by Southwest (SXSW), Edible Magazine, Westchester Magazine, Refinery 29, the Art Directors Club, AIGA and more.

Justin is a two-time winner of the International Design Awards, American Photography and Latin America Fotografia. Vice News has called Justin Negard as “one of the best artists working today.”

He is the author of two books, On Design, which discusses principles and the business of design, and Bogotà which is a photographic journey through the Colombian capital.

Additionally, Justin has served as Creative Director at CityMouse Inc., an NYC-based design firm which provides accessible design for people with disabilities, and has been awarded by the City of New York, MIT Media Lab and South By Southwest.

He lives in Katonah with his wonderfully patient wife, son and daughter.