When artists refuse to be confined to galleries, the public space becomes their canvas, and we become the curators.

By Liz Colombini

I have become a walking art gallery, but that was never my intention. Covered in tattoos from my neck to my ankles, I’ve watched strangers become unwitting critics in grocery store lines, coffee shops and restaurants. They glance, they stare, they whisper to their friends, and they approach with questions, compliments or barely concealed judgment. I never asked them to curate my body art, but the moment I step into a public space, that’s exactly what happens. That got me wondering: What about all the other art we encounter whether we want to or not? The mural that interrupts your morning commute, the elaborate nail art on a barista’s hands, the thought-provoking sticker on a lamp post while you walk down the street. We all become accidental art critics, thrust into the role of viewer and judge for art that refuses to quietly stay in galleries or museums where we can choose whether or not to engage.

Art at your fingertips

Art in public spaces can appear in the most unexpected places. Genesis Rodriguez, owner of Geni Nails Studio in New Rochelle, understands this phenomenon better than most. For her, every client becomes a walking gallery. “Each client leaves here as an exclusive exhibition,” she explains in Spanish. “And the best part is they don’t need an entry ticket. They themselves are the gallery.” One quick look at her Instagram page reveals thin strokes of color delicately applied to each nail. Jeweled, glossy and shimmering, the nails invite viewers to take a closer look.

- Nail designs created at Geni Nails Studio.

Her observations reveal the true nature of this unintended audience dynamic: “It happens a lot… suddenly someone in the supermarket line transforms into an art spectator and says, ‘Wow, how beautiful, what technique, where did you get them done?’ And of course, my clients are happy to show off their work of art.”

But for the Venezuelan-born artist, her most striking insight captures the essence of mobile art. “Art on a wall stays put,” she says. “My art, on the other hand, drives, pays bills, sends messages and even grabs the shopping cart at the market.” Because her work participates in daily life, it creates countless micro-encounters between strangers and art they never chose to see.

For Rodriguez, her art is more than decoration. “This isn’t something common,” she notes. “This isn’t something you can go anywhere and have anyone do for you. No, this is passion; this is art; this is dedication; these are years of work and years of practice. And above all, I do it with love.”

The living canvas

What if your art were permanently wearable? While nail art can be changed with different colors, embellishments and glitter, tattoos are forever. This art medium becomes part of the body, carried through daily life, making interactions between tattooed individuals and observers a form of mobile art that has spread worldwide. “When you’re a tattoo artist, it’s a little bit different, because you’re not necessarily doing an art piece for you,” explains Chuk Högnell, owner of The Mighty Horseman Tattoo Co. in Yonkers. “Your skill set and talent are there to create what somebody else wants or what they want to convey. It means something to the person who has it, not necessarily to you, the artist.” Högnell, who has created body art for over two decades, believes there are complex social dynamics at play; he’s witnessed the same art form provoke vastly different reactions depending on who displays it.

- A selection of tattoos from The Mighty Horseman Tattoo Co.

Högnell says that while he doesn’t often hear about the public’s reaction to his artwork, when he does, it’s typically positive. “As long as my client is happy, I couldn’t care less what strangers think. I created that work for that one individual, not the rest of the world.” But this evolution isn’t uniform. It depends on who’s wearing the art and where they’re encountering the public. Högnell’s own experience illustrates this perfectly. At 6’4” and 240 pounds, with a braided beard and Nordic tattoos adorning his massive frame, he resembles a modern-day Viking warrior, a presence that rarely invites direct judgment. “People don’t break my bones very often,” he laughs. “They look at me and they’re not gonna be like, ‘Why do you have tattoos?’” However, his wife presents a stark contrast. “She’s fairly heavily tattooed, but she’s also in banking and real estate. So she kind of gets a little bit more of that.”

Högnell says tattoos may influence someone’s initial perception, but those impressions often change once you start talking to them. “People say things like, ‘Oh, I saw tattoos. I didn’t think you were as well put together as you are.’ But that’s life. You’re going to see things you may or may not like when you venture outside your front door. I’m not making art that would be considered offensive, but, although considerably rare these days, you may find people offended by tattoos. However, that has to do more with tattoos in general rather than the work itself or the subject matter; they’re just going to hate it regardless.” When his wife faces professional judgment, “she’ll just kind of spin it on people,” he says, describing how she engages critics in conversation until “they drop their BS.”

Reclaiming visual space

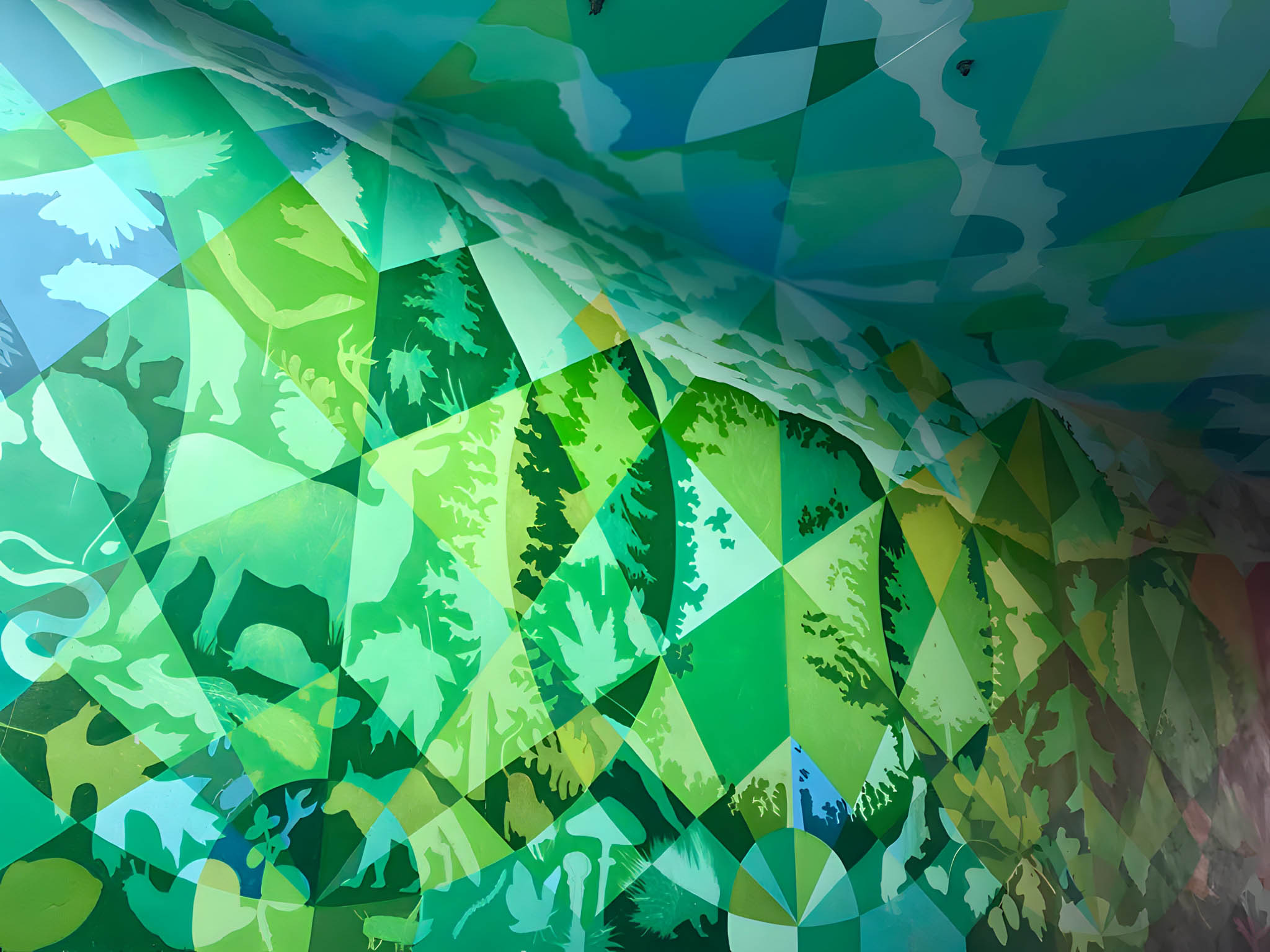

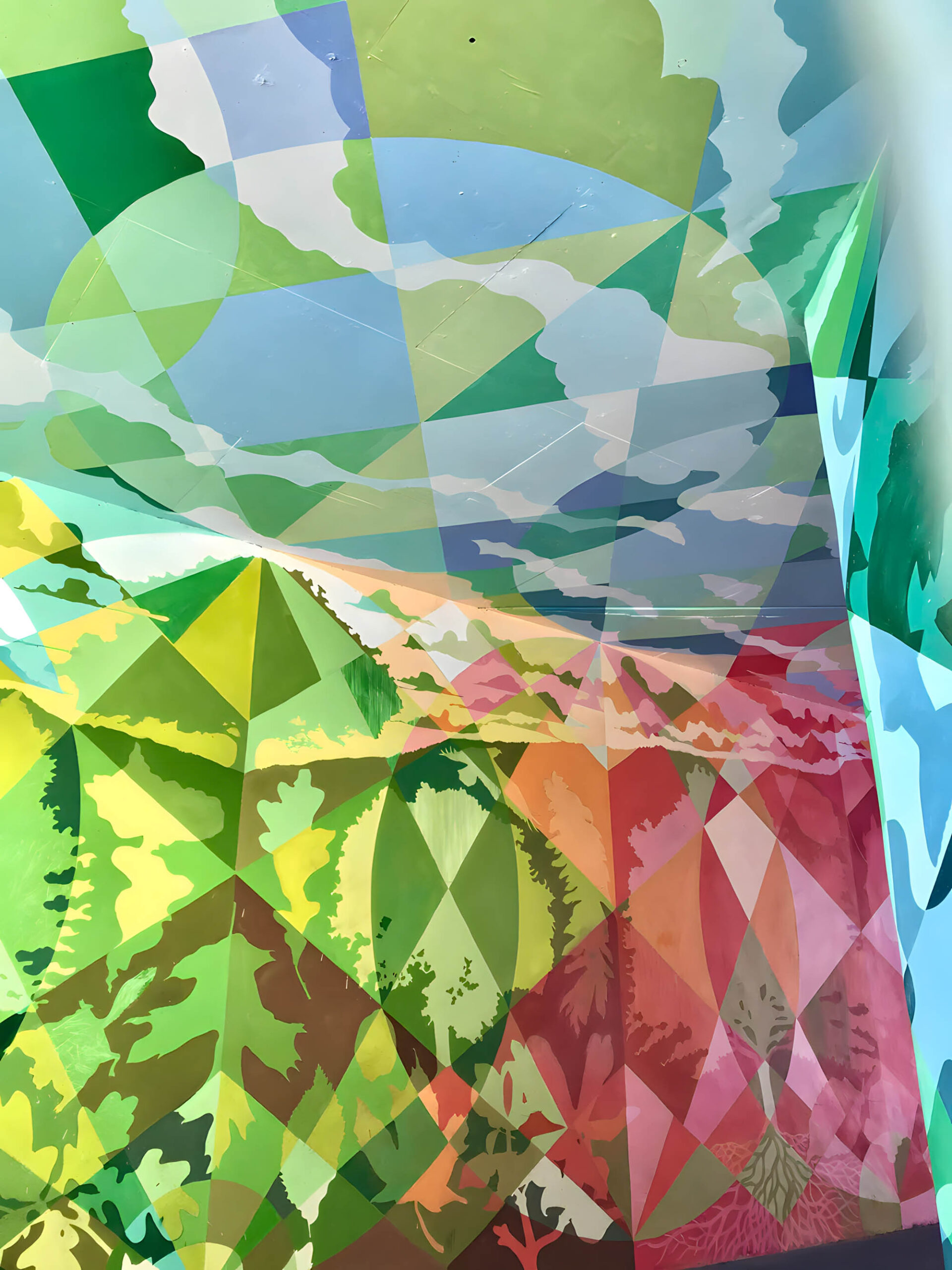

If you’ve driven across the Governor Mario M. Cuomo Bridge, you might have noticed the bright multicolored abstract mural on the walking path created by Chris Soria. Soria, a muralist with 20 years’ experience legally painting walls across New York City’s five boroughs, sees public art as a necessary counterbalance to commercial visual pollution. “We’re all proliferated with advertising, as well as, you know, thought-programming by the various corporate entities and powers that be who have those resources to commandeer our visual space,” he notes. “So all the more reason why I want things to have more inclusivity and more variety of thought and philosophy.”

- Chris Soria multicolored abstract mural.

But Soria is acutely aware that his audience doesn’t always choose to encounter his art, even though many seek out public art and make it a destination in their travels. When working on public pieces, he constantly considers the unwitting viewers who will pass by. “When I’m developing and creating public artwork, I’m always aware of how people will encounter and engage with it,” he explains. “People will see this and think, ‘Who lives there? Who passes by?’” And knowing that will likely go through a driver’s mind, Soria says he works within specific parameters. For his mural in the bridge’s tunnel on the shared bike path, Soria painted within certain constraints, creating work that he says would “lean a little bit more abstract and not be something that’s going to distract drivers.” Even while exploring the biodiversity of the lower Hudson Valley, he must balance artistic expression with public safety, ensuring his unwitting audience can safely ignore his work if they need to focus on the road.

“When I’m developing and creating public artwork, I’m always aware of how people will encounter and engage with it,” he explains. “People will see this and think, ‘Who lives there? Who passes by?’”

The difference between chosen and accidental art encounters isn’t lost on him. “I would hope that my art is often contributing something unique to the daily thought process of a commuter that is on their way to work,” he says. Unlike gallery visitors who actively seek artistic experiences, his audience consists of people simply traveling. Yet his art becomes part of their routine, inserting itself into their consciousness whether they planned for it or not.

Working for audiences who can’t choose to leave, unlike museum-goers who can simply walk away from challenging work, requires a different kind of responsibility. His art must coexist with people’s daily lives rather than demanding their full attention or challenging them beyond their comfort level during a morning commute. “My work is somewhat palatable intentionally,” he admits. “I’m not a controversialist. I’m not Banksy.”

The documentation dilemma

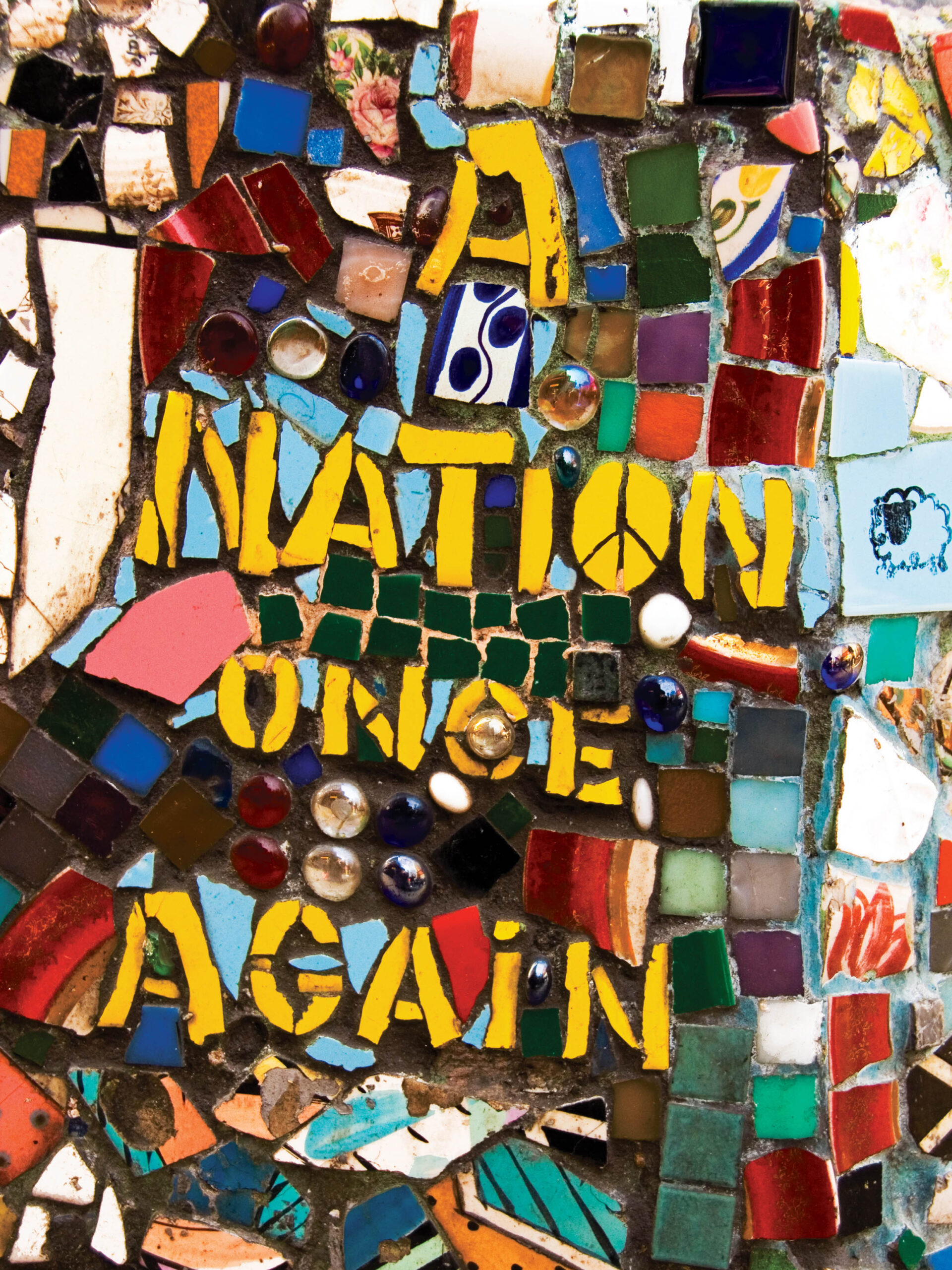

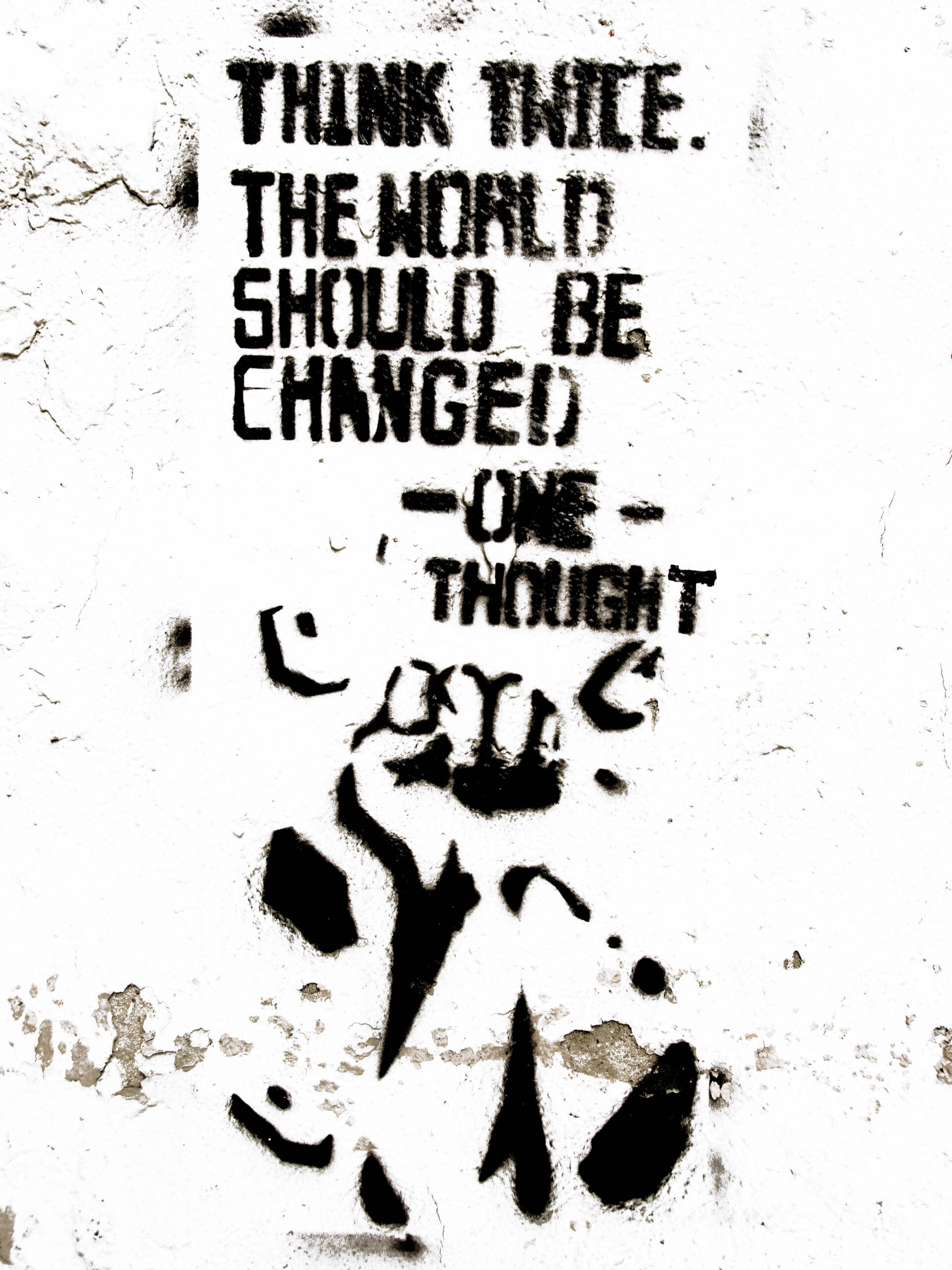

Helena de Vengoechea Rudd’s “The Museum of Messages” reveals another layer of the unwitting audience experience. Drawn to what people scrawl or draw in an urban setting like lampposts, utility boxes and even other people’s signs, Rudd, who lives in Pound Ridge, began a photo project in 1999 that documents strangers’ thoughts about things like the environment, love, politics, humor, self-expression and more. After 12 years of photographing street messages throughout New York City, she understands the tension between preservation and spontaneity. “I started the Museum of Messages because there were several times when I saw messages that made me laugh or think differently,” she explains. “Since I carry my camera everywhere, I thought, ‘I’m going to photograph, exhibit and publish these messages for others to see, so they can laugh, think, get a different perspective on what the artist is saying and [they can] grow.’”

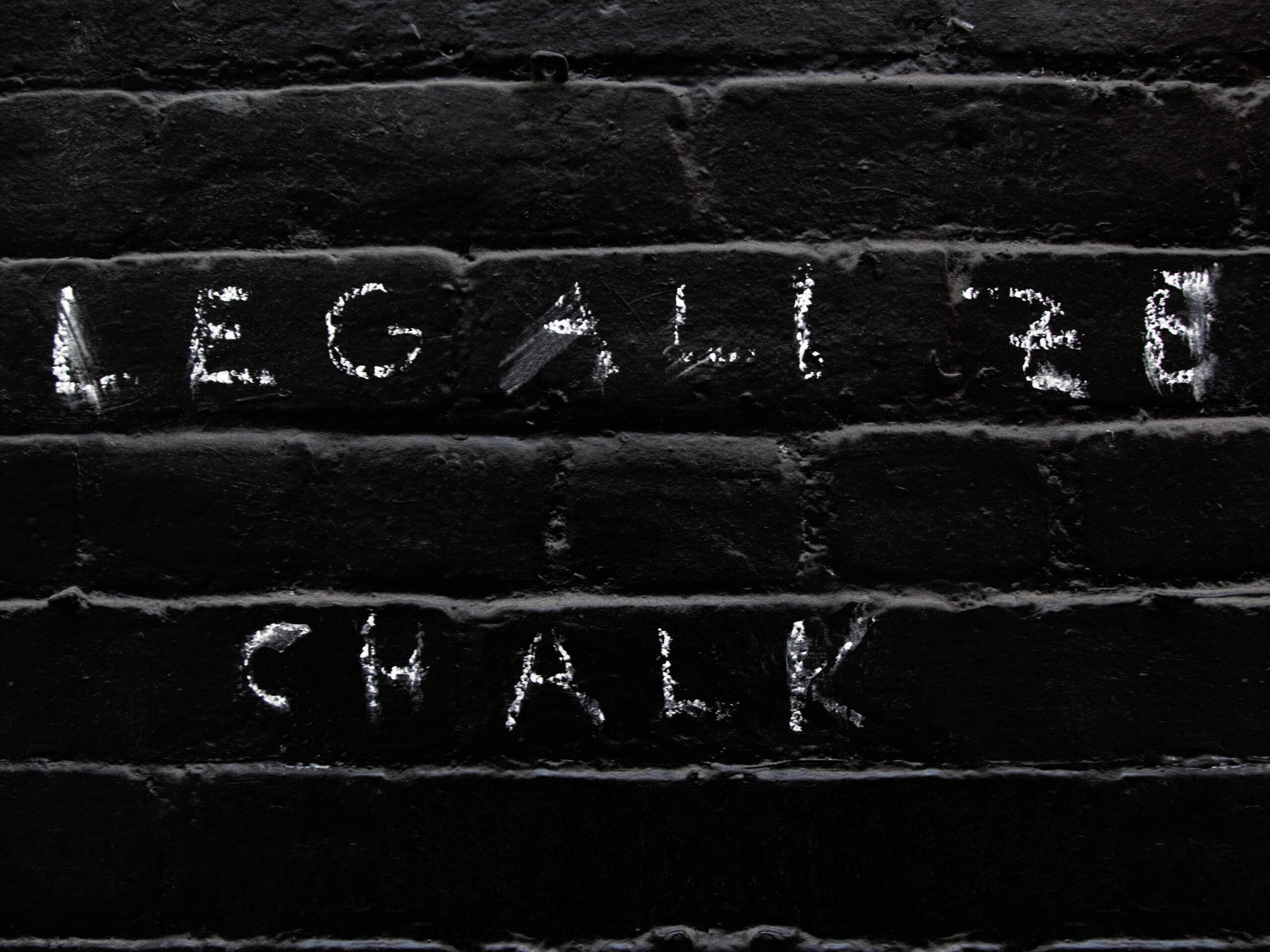

“That’s pretty brilliant,” she says, “because chalk is so easy to clean up. All you have to do is throw water on it and it goes away.”

Rudd’s work blends the concepts of accidental (herself) and chosen (her viewers) art encounters. “I love it when messages grab my attention when I am out and about. Especially the ones about love,” she says. “When you view my photographs online, the messages are a collection. There is more of a connection, a growing experience, when you see them in person.” She lights up when talking about some of her favorites. “One morning while walking through Union Square, I encountered a young man holding a ‘Free Hugs’ sign. The moment struck me as spontaneous and powerful, someone offering human connection to strangers passing by.” Sometimes the messages make her laugh, like the one that read, “Legalize Chalk.” “That’s pretty brilliant,” she says, “because chalk is so easy to clean up. All you have to do is throw water on it and it goes away.”

- A selection of photographs from the Museum of Messages.

Street messages, Rudd believes, can serve as forms of encouragement during difficult times. “Life is very wonderful, but there are downs,” she explains. “And maybe somebody can cheer you up with a phrase.” She’s drawn to works like “Love Love Love,” which features a woman in a yellow hat walking past a window (“It strikes me as strong.”), and “Paradox I Love You,” showing a man in a red hat and black jacket walking by a lamppost. “I also love ‘Peace and Love’ because we need that in the world,” she says. Artists, Rudd believes, create public messages to “wake people up and brighten people’s lives.”

Rudd says she documents these messages because they’re “visual voices that want to be heard. As an artist, my goal is to archive these visual voices so others can think, learn and continue to grow on this journey of life.” Her work, which can be seen online at themuseumofmessages.com, can also be viewed in person at Ridgefield Bagels & Bakes until the end of December.

The unintentional observer

The spontaneous discovery, the unexpected interruption of routine, the inability to simply walk away—these elements give the viewer more of a connection to the art than they might have if they viewed the same work in a controlled environment.

In a world increasingly dominated by corporate messaging and digital screens, these artists are quietly insisting that authentic human expression deserves a place in public space. They’re betting that even unwilling audiences, given enough encounters with thoughtful creative work, might eventually stop and really see what’s been in front of them all along. They’re turning us all into unwitting curators of a gallery that exists everywhere we go, reminding us that art doesn’t need our permission to matter…it just needs us to be human enough to notice.

This article was published in the November/December 2025 edition of Connect to Northern Westchester.