Experts share how schools should prepare students for an AI-oriented workplace. It’s probably not what you think.

By Alexa Berman

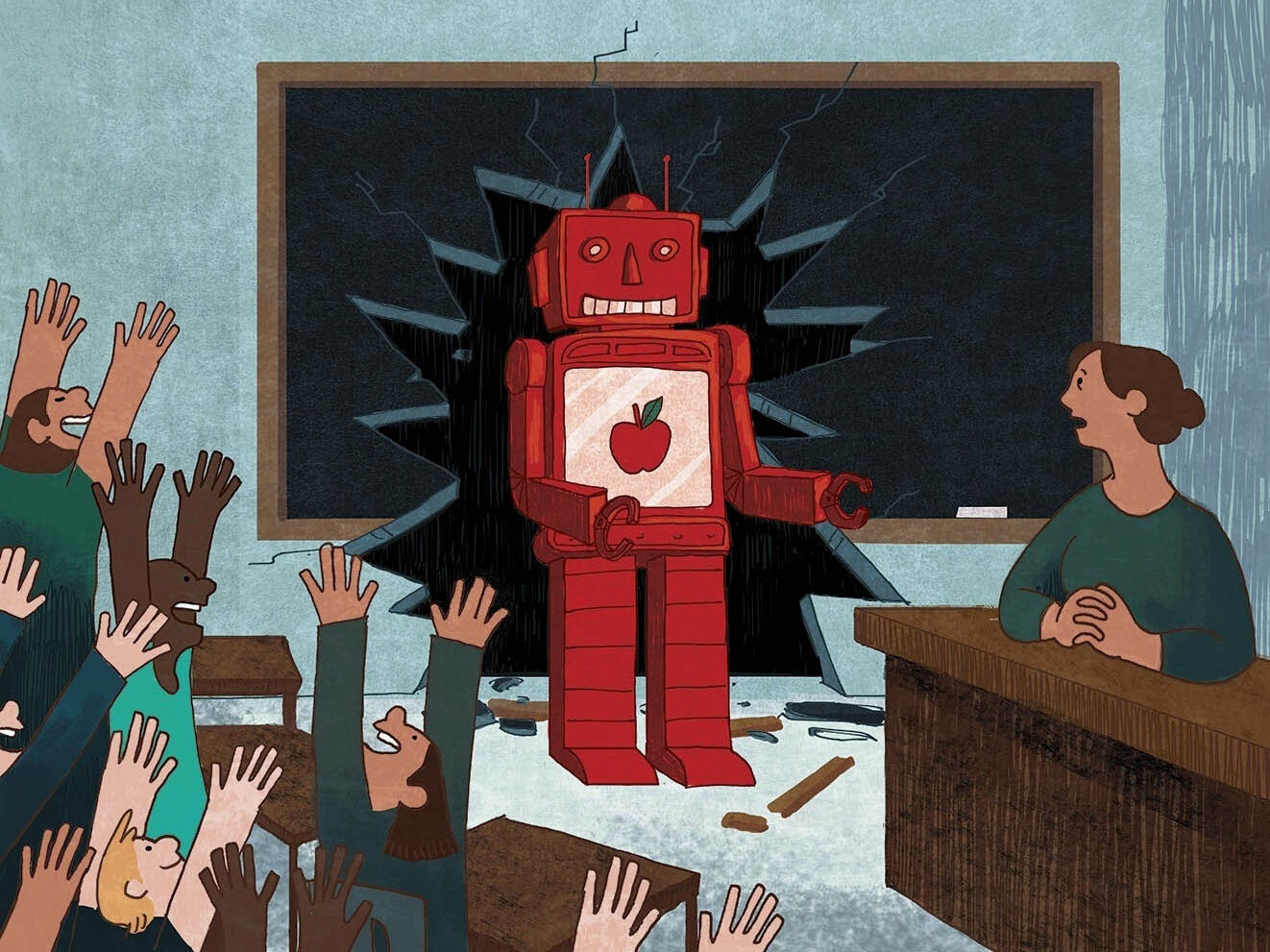

Artwork by Anne Kennedy

When it comes to artificial intelligence, most of us fall into three camps: fully onboard, tentatively curious or actively avoiding. Regardless of where you stand, the reality is AI is here to stay, and it’s changing the workplace… fast.

In fact, according to the World Economic Forum’s 2025 Future of Jobs report, AI and other emergent technologies are expected to displace nine million jobs in the next five years, but they will create new ones too. The report goes on to say that by 2030, this technological revolution will lead to approximately 11 million new jobs. The experts we spoke to say many of the new industries require very little, if any, knowledge of coding or computer science. However, there are still important skills to learn, which should start in school. Now you’re probably wondering, “If students aren’t learning to code, what should they learn?”

Well, we’re glad you asked.

Now hiring

Before we talk about classrooms, let’s discuss what the future workforce might actually look like. According to industry experts, such as Kathy D’Agostino, an AI skills trainer and strategist at the White Plains-based Win at Business AI, middle management and entry-level positions—likely in finance, marketing and legal services—will be the first to go. According to a 2023 study by McKinsey Global Institute, many customer-facing roles, such as office support, customer service and food service jobs, could see declines. These jobs often involve repetitive, predictable tasks and lack creativity and empathy, making them easier to automate.

But there’s good news, too. Robert Seamans, a professor at NYU’s Stern School of Business who studies the economic consequences of AI, sees three especially promising roles on the rise: AI integrators, AI auditors and AI translators. Here’s what they’ll do:

Integrators will implement AI into existing systems and optimize its performance.

Auditors will keep tabs on what AI is doing and why—for liability, transparency and quality control.

Translators will act as liaisons between AI systems and the rest of the business, explaining complex processes in plain language.

“For these three jobs, there are two important sets of skills that one needs,” Seamans explains. “The first is a bit of technical expertise. An AI integrator, for example, needs the most technical expertise. That’s also crossed with domain savvy, as an integrator in a banking setting would have different goals than an integrator in the retail industry. But for the AI translator, good communication and people skills are most important. The idea is that the person knows enough to understand the way the AI system is working, but they can talk about it in a non-technical way with managers or a CEO.”

In the shorter-term job market, Seamans says the AI plumber will be an in-demand role—someone who installs, maintains and fixes AI systems inside a business’s tech ecosystem. “Right now, these positions are in short supply, which makes them incredibly valuable,” Seamans explains. “But as more people gain the necessary skills, and as better tools emerge, these jobs will likely become more commoditized, much like web developers were during the early days of the internet.”

But you don’t need to land a tech job to get acquainted with AI. In fact, most of us will encounter it no matter what career path we choose. “There’s no question in my mind that most workers, especially white-collar professionals, will need a basic, if not a relatively mature, understanding of AI within the next five years,” Seamans says. “It will likely become a daily part of their work. Right now, AI still feels confined to a small group of trained users, much like the internet did 15 or 20 years ago. But soon, it will be embedded in the majority of jobs.”

The reality is, AI is no longer something reserved for Silicon Valley masterminds and computer science whizzes; it’s a resource available to all of us, and therefore something worth getting to know. “Before November 2022, AI was this very specialized technology, but once ChatGPT went public, it became information for anybody to use,” D’Agostino points out. “You don’t have to learn how an LLM (Large Language Model) works. You just have to know what your job is and how AI can help you optimize it.”

The democratization of these tools underscores a need for technological literacy—something less focused on deep coding knowledge and more about practical application and strategic integration. “So, how do we get from where we are right now to five years into the future?” Seamans asks. “By integrating AI into education and teaching.”

Optimizing the classroom

Experts agree that introducing AI early is the first step. Christelle Scharff, professor of computer science at Pace University and director of the Artificial Intelligence Lab, says children should be introduced to AI in middle school, and possibly even earlier: “As soon as students have presentations or research-related projects, they should learn how to use AI correctly,” she emphasizes.

All three of the experts agree that AI literacy is also about teaching the soft skills AI lacks, such as critical thinking and emotional intelligence. “AI literacy is not just about how to use AI,” D’Agostino explains. “Kids will figure that out themselves. It’s about grasping the basic concepts of pattern recognition, fairness and decision-making.” In other words, the humanities are key. Classes in literature, history and social sciences lay this groundwork. D’Agostino puts it plainly: “If kids skip the foundational thinking, they’re going to short-circuit their comprehension.”

Fake news, real skills

These soft skills—like critical thinking—aren’t just helpful; in an AI-powered world, they’re essential, especially when it comes to one of AI’s biggest pitfalls: misinformation and bias. “There’s one thing that always stays constant with new technology use: being critical of all the information put in front of us,” says Scharff. This analytical eye is crucial when the technology can easily generate convincing, yet potentially flawed, content. “When coming across pictures, videos, or text online, the first thing we should ask is always, ‘Is it real? How do I know?’” Scharff continues.

Take, for instance, the many cases where AI hallucinates false dates, research and even citations, leading to embarrassing outcomes—Steven Schwartz and Michael Cohen are great examples. D’Agostino equates these AI responses to an incomplete first draft when writing—incomplete and in need of revision. She says she often challenges AI accuracy by asking the chatbot to rate its responses and correct itself when needed. “AI is very good at being critical of itself, if you ask it to do that,” she explains. “The best part is, it’ll say, ‘Would you like me to make some corrections and fix that?’ This is a vital skill for kids to learn in school; they need to understand where the technology falls short and gauge how to correct it.”

Yet, “when many students use AI now, they prompt a question and then copy and paste the first answer,” Scharff observes. “But that’s not productive for learning. If you ask a question, it’s important to read the answer, cross-reference it with other sources to fact-check it, and explain it back.”

Scharff says teachers should incorporate fact-checking exercises into their lessons so students can evaluate AI-generated content for bias and false information. She has introduced this to her students through facilitated experiments. In one, Scharff asked ChatGPT to write a public figure’s biography, then she challenged students to underline any inaccuracies and explain what’s missing. In another activity, Scharff asked students to feed visual prompts into an image generator—like “toys in Iraq” or “African doctor caring for white children.” The results were telling: “Often the AI-generated pictures showed war-related toys and children dressed in army clothing. And the tool was actually never able to generate a valid image of African doctors caring for white children; instead, the children were Black. These experiments led to conversations around bias, representation and fairness, which were key in teaching empathy.”

These discussions don’t just make students better thinkers—they could even lead to careers. A student who’s naturally empathetic and detail-oriented could become an AI fact checker, ethics consultant or sensitivity reader—roles essential to keeping these tools fair, safe and inclusive. These professionals could also work on increasing representation among AI models and making them accessible to people across languages, backgrounds and varying abilities.

D’Agostino enforces critical thinking in her day-to-day engagement with AI by building prompts into the systems so they cannot go “off the rails” and give false information. When talking with a chatbot, she might use commands such as “clarify first,” where the AI must ask questions before jumping straight to answers, or “facts only” to ensure objective responses. These guardrails help her discern between fact and fluff. “AI wants to jump in and please you, so we must always pause before accepting an answer as truth,” she says. Even with guardrails, fact-checking and a critical eye are still paramount.

D’Agostino adds that children should also produce their own ideas before turning to AI, which will help them build independent thinking skills. “Children have limited decision-making skills,” she explains. “They’re not pulling from past experiences, per se. So, it’s important for teachers to guide their students to be curious first. This way, kids won’t become overreliant on AI.”

Human intelligence required

Beyond individual critical thinking, Seamans also emphasizes social skills and collaboration as a key component of safe and productive AI literacy in schools. “AI is trained to interact with individuals and optimize what each person is doing,” he explains. “Yet so much of human work and socializing is not on a singular level but on a group or team basis.” For example, apps like Spotify or Netflix excel in predicting individual preferences but cannot adapt to collective tastes. “Spotify does a great job of predicting music for me, and it does a great job of predicting music for my wife, but it doesn’t necessarily do a great job of predicting music that we would like to listen to together,” Seamans says. “I worry that it’s so easy to predict what works for an individual, but ultimately, we are a society, and so much happens in groups and teams.”

That’s where social skills still matter. “There’s a risk that kids will substitute human learning and connection for synthetic relationships, so it’s important to reinforce peer collaboration,” D’Agostino explains. “Rather than using AI alone, kids should use it as a tool for group discussion to help facilitate conversation and healthy social dynamics between students.”

Like teamwork, empathy is another skill crucial for dealing with AI, especially at a young age. Scharff reinforces this with her students by testing AI and its language recognition capabilities, which ignites discussions over equity and fairness in these systems. “For example,” she says, “we experimented with different ways of communicating with the AI, using multiple languages, diverse accents, and even speech impediments that aren’t ‘standard’ English. When AI fails to recognize something, students then wonder, ‘Why is this happening?’ and ‘Where is this problem coming from?’”

A student who enjoys this conversation about fairness and bias might consider a role as an AI ethicist or policy expert, as these roles will recognize bias across AI systems and ensure compliance with regulations. Additionally, according to the World Innovative Sustainable Solutions’ March 2025 report, those with strong social skills might consider roles in patient care, as the healthcare system turns to AI for more administrative work, or even anti-escalation roles that help manage emotional or complex conversations that AI can’t yet handle.

Preparing for the AI age is not about predicting every specific job or technological innovation. Instead, it’s about nurturing a resilient, adaptable and critically engaged generation. “I think there’s a lot of learning by doing, so it’d be a mistake to wait until we have everything figured out,” Seamans says. “By encouraging educators to move forward and continue discussing these tools with students, we will learn a lot faster rather than waiting for every issue to work out before incorporating it into a curriculum.”

D’Agostino compares AI to an entry-level employee. “Just like a new employee often makes mistakes and requires training and mentoring, AI needs the same in the early stages,” she says. “We can’t just fire them because they make one mistake; instead, we give them more help.”

In other words, don’t panic, but don’t sit still either. Whether you’re a teacher, student, parent or just someone wondering what’s next, the best way to get ready for the AI age… is to start. Ask questions. Experiment. Get curious. Because the future isn’t just being built by tech—it’s being shaped by how we choose to learn, think and grow with it, regardless of our age.

This article was published in the September/October 2025 edition of Connect to Northern Westchester.