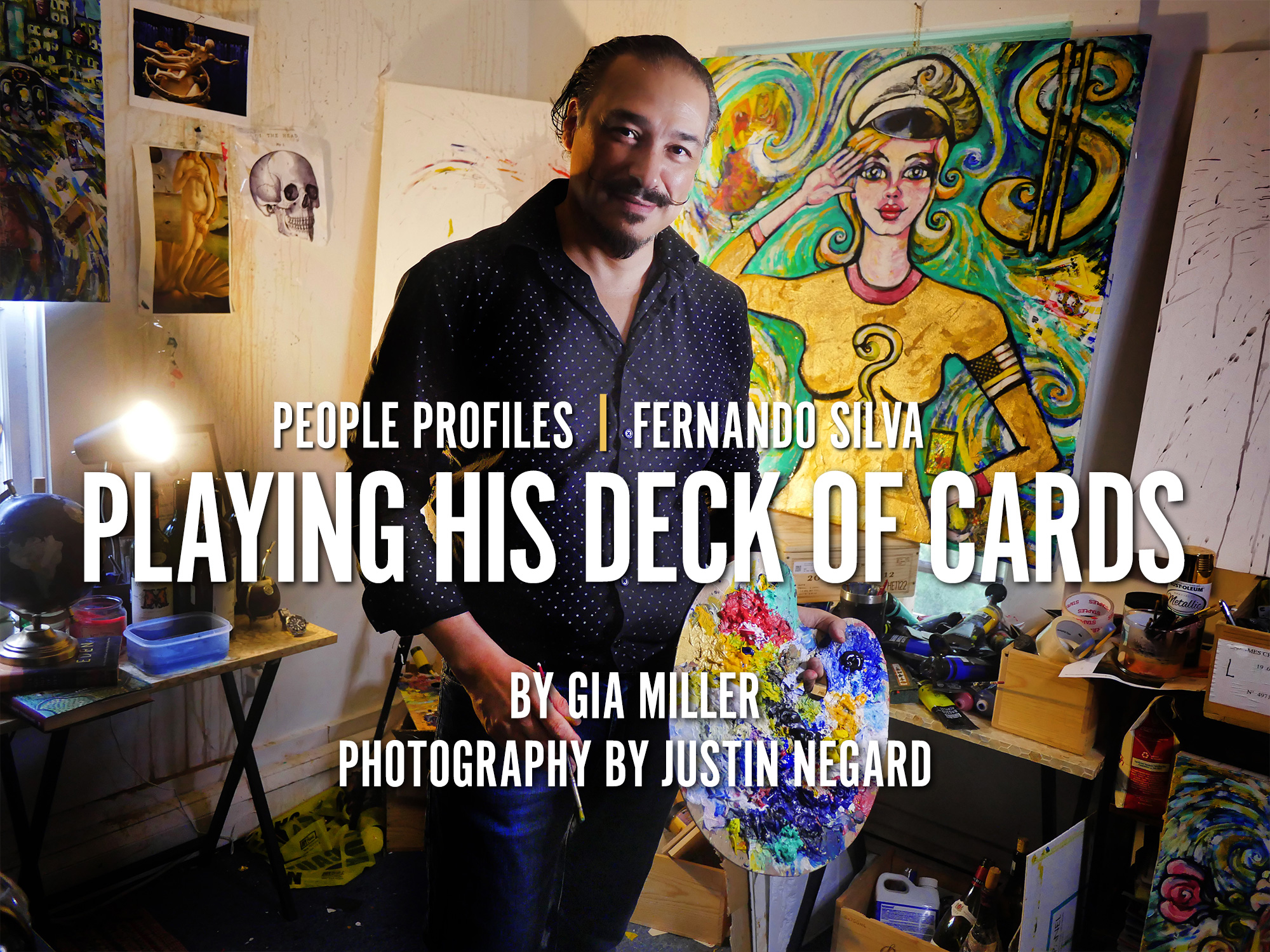

One Saturday morning in early November 2020, Fernando Silva, the wine director of Bedford’s Glen Arbor Golf Club, was at home when he received a phone call from Grant Gregory, the club’s president.

“He asked me if I was around the next afternoon,” Silva recalls. “I said yes. Then he asked me if I could bring my best paintings to the club because a special friend of his was coming to play golf with his friends, and he wanted to honor them with a little private show. So I said, ‘Yes, of course, sir.’”

Silva arrived at the club around 11:30 a.m., set everything up and then waited. At 2:00 p.m., Silva texted Gregory.

“I told him I was at the club and asked if he was coming soon,” says Silva. “He texted back and asked if everything was set. I wrote ‘yes.’ He replied, ‘Perfect.’ And that was it. Radio silence.”

Ten minutes later, President Bill Clinton walked in and asked the receptionist if Silva was there. She told him that Silva was upstairs, and then she went upstairs to tell Silva that Clinton had arrived. Silva was shocked – he didn’t know who the show was for. He told the receptionist to send him up.

“He came upstairs with 10 or 12 people and asked me, ‘You’re Fernando?’ I replied, ‘Yes, sir.’ He said, ‘You are the artist and the sommelier?’ I replied, ‘Yes, sir.’ ‘Good, good,’ he said. ‘We’re here to see your artwork. These are my friends.’”

As they began looking around the room, Clinton asked Silva to tell him about his work. Silva walked with Clinton, describing the various paintings until Clinton stopped at a 40” x 40” painting, turned to Silva and asked, “Why did you make this one?”

“It was around the time Sean Connery passed away, and I told him I was inspired by James Bond,” Silva explains. “Then President Clinton turned around, put a hand on my shoulder and said, ‘I want you to listen to a story. Back in the day, I met Sean Connery at a Hollywood gala, and we clicked. I told him I wished I was James Bond, and he told me he wished he was the president of the United States. It became our joke with each other. We spent a lot of time together and became very, very good friends. Two days before Sean Connery passed, he called me. He knew he was going to pass.’”

“President Clinton got very emotional,” Silva continues. “And then he said, ‘I’m speechless. Thank you very much. You’re a great artist.’ It was a very strange moment. Then he started to leave, and everybody followed him out. They shook my hand, told me my work was great and thanked me for my time.”

“Then, as the whole entourage was going downstairs, Clinton turned around and came back up. He got close to me and whispered, ‘How much do you want for that painting?’ I said, ‘Mr. President, I want your friendship. How about that?’ He replied, ‘You got it.’ He shook my hand, gave me a hug and took my painting. It’s now hanging in his office, and that experience will be with me forever.”

Now, whenever Clinton sees Silva at the club, he shakes his hand and says, “My artist.” Silva responds, “My president.”

The early years

Growing up in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Silva’s aunt took him and his two siblings into the city on Sundays “for a stroll and to check out the museums.” Silva was fascinated by the art and would try to copy what he saw when he returned home.

“I was terrible,” he remembers. “It was awful. But I was so enthusiastic about learning to draw and paint that when I was 11 or 12, my aunt signed me up for an art class. Unfortunately, the teacher was very disappointed with my art. He said, ‘You can’t even draw an apple or a banana. This is terrible. This is not for you.’ So, I stopped.”

At 19 years old, Silva became a waiter on a cruise ship and spent three years traveling the world.

“One of the last ports I visited was New York,” he says. “When I started walking around the city streets, I fell in love. I knew it was where I wanted to be.”

Silva returned home, finished his degree in hospitality and landed a job at BallenIsles Country Club in Palm Beach Gardens, FL towards the end of 2004. He went from dishwasher to waiter in one month, became a head waiter two weeks later and then began serving the VIP tables. One night, unbeknownst to him, he waited on a group of headhunters from New York who were recruiting for a five-year-old golf club in Bedford Hills. They hired him, and he moved to New York in the spring of 2005 to work at Glen Arbor where, initially, he did a bit of everything.

“After a few months, Mr. Gregory came up to me and said, ‘Didn’t I see you behind the bar the other day? Are you doing tables now? I want to talk to you.’ We sat down, and he said, ‘I’ve been watching you, and I like what you do. I like your dedication. What can I do to keep you here forever?’ I responded, ‘A green card would be nice.’ Long story short, I got the green card, and I’ve worked for them ever since.”

Finding new inspiration

Because Glen Arbor was closed between mid-December and mid- March, Silva spent that time visiting Manhattan’s art museums, and he decided to give art another try. He purchased supplies and turned to YouTube for instruction. With the help of a variety of virtual teachers, including Bob Ross, Silva learned how to paint.

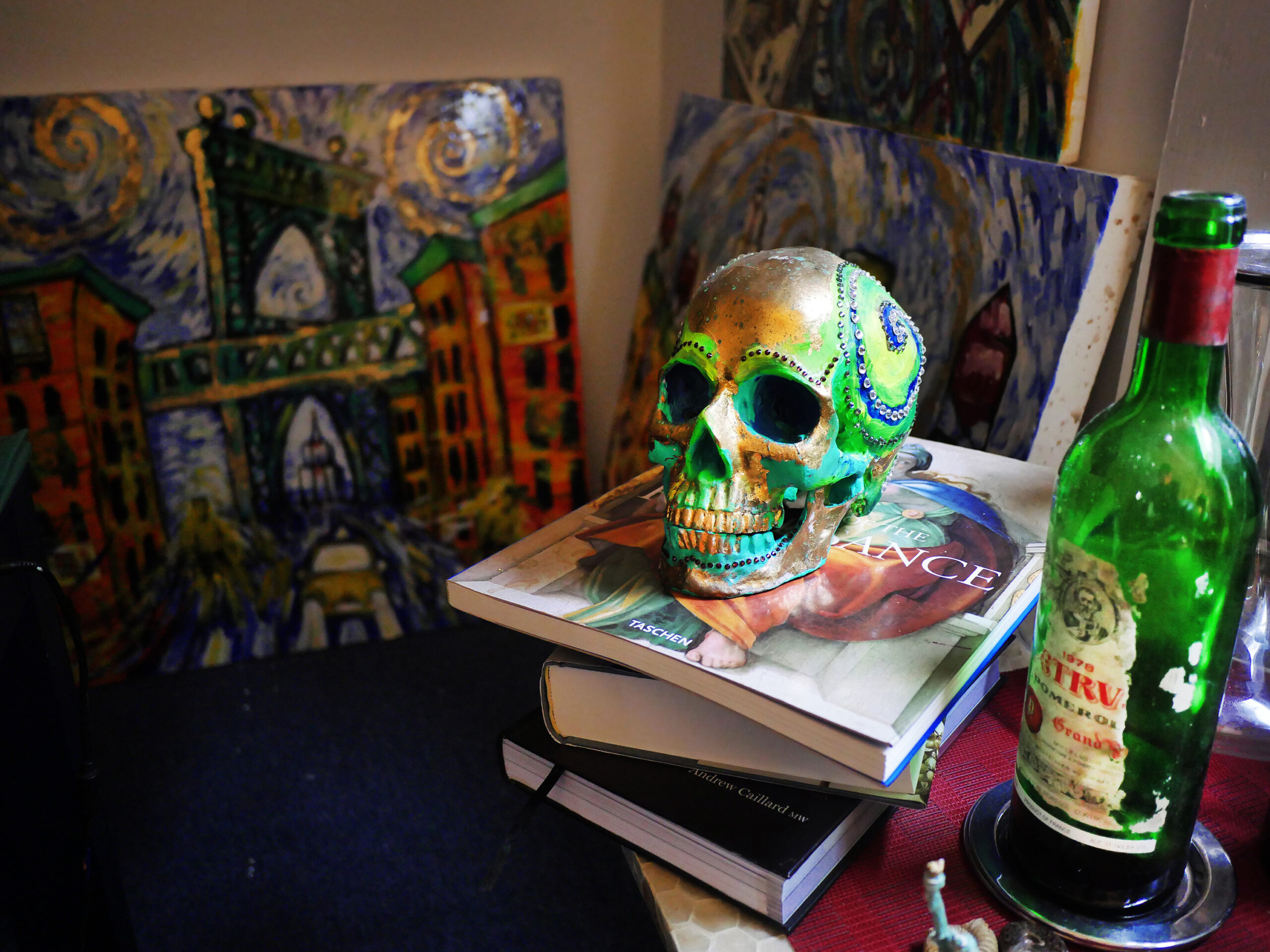

Five years later, when the time came for Silva to leave the country during the green card process, he went to Germany with the woman he was dating. While there, her parents noticed his interest in art and took him to the museums in Paris. He was drawn to the impressionists, specifically Gustav Klimt.

His girlfriend’s parents were also wine connoisseurs, and they helped Silva develop a passion for wine. After 10 months in Germany and two months back home in Argentina, Silva legally returned to New York in 2012 with a new passion: wine. Once again, he turned to YouTube to learn more.

Silva saved money and began taking wine courses during the winter months. He studied at the French Culinary Institute in SoHo and the American Sommelier Association. Because he could only take classes during those months, it took him several years to earn his Court of Master Sommeliers certification. That summer, he approached Gregory about creating a wine program.

“I told them that most of their members are very savvy when it comes to wines, but the club is missing a wine program and a wine cellar,” he says. “I explained that I wanted to create a program for them as a thank you for sponsoring my green card.”

That winter, Gregory invited Silva to his house to discuss Silva’s ideas for the program. “He asked me to write down 20 ideas on how to create a wine program and said he’ll see what they can do. I came back with about 30 ideas, and we’re continuing to implement the ones that are a good fit for the club.”

One fateful afternoon

In December of 2013, Silva received a call from one of the club’s golf professionals who was on vacation. He told Silva that a member left his golf clubs at Glen Arbor, and he wanted to pick them up before he flew down to Florida. Silva gladly agreed to help out. At the club, he placed the golf bag inside the front door and then brought his easel and paints to the back patio to paint the landscape while he waited.

“The member parked his car on the side of the building and came in through the patio,” Silva remembers. “He saw me painting and said, ‘I didn’t know you paint.’ I told him it was my hobby, and he said, ‘Let me see that.’ He asked me if he could take a picture of my work. I thought he was crazy, but he said he really liked it and wanted to show it to his wife who was a retired curator at Gagosian, a gallery in Manhattan. Then he told me that they were making a short trip back to New York in January and I should bring as many paintings as I have to the club for her to see.”

The next month, she critiqued Silva’s work, telling him what was okay and what he should never do again. Then, she selected three pieces that included painted swirls, and told him this was the style he should continue. A week later, she called to say that she arranged for him to join a show at Gagosian in March. But just a few days before the show, there was a fire in Silva’s home, and he was only able to save 15 of the 40 paintings he’d made. He selected four of those pieces for the show and sold three. It inspired him to buy better materials, and word began to spread about his art.

“A year later, the owner of the club came up to me and said that a member mentioned I’m an artist, and he asked to see my work,” says Silva. “He was very, very impressed. I started creating postcards for the club, which were mailed to all the members. Meanwhile, a painting sold here, and another sold there, and I got connected with a gallery in California that helped me get my paintings into Art Basel in Miami every other year.”

Silva also began teaching two art classes per year at the club – one for adults and one for children. He also holds an annual art show at the club for his adult students.

And then, as all stories go these days, COVID-19 happened.

Finding his voice

For Silva, 2020 was his most productive year. It’s also when he transitioned from copying others’ work to finding his voice. But prior to the pandemic, he began his first painting ritual, which, of course, involves wine.

“One night, I came home from the city really inspired by the wine tasting I attended, and I grabbed my brushes and started to paint,” he remembers. “I had a glass of wine in my hand, I made a little swirl in the glass, and boom – it splashed onto the canvas. I looked at it and said, ‘Okay, wait a second – this is not bad.’ So, I took my brush and made a swirl here and a swirl there, and then I start painting. And so, since that moment, it became my ritual before I begin to paint.”

Silva paints on Tuesday, his day off, or when he comes home from work in the evenings. But even if he’s home during the day, he can only paint at night, often finishing around 3:00 in the morning.

“Sometimes I can do a painting in five or six hours,” he says. “I’ll paint for about three hours, take a break, come back an hour later, and paint for three more hours. Then I will go back two or three days later to retouch it.”

His inspiration, he says, comes from the heart.

“I think it’s possible to be conscious in every waking moment, but it’s impossible to always be present,” he explains. “When I am present, I realize that a moment doesn’t last forever. I try to capture those moments on the canvas so they will stay forever.”

He typically paints on large canvases (30” x 30” or 40” x 40”) with acrylics. A single painting has anywhere between 10 to 20 layers of paint; and because it can be difficult for him to stop adding to his work, he often adds a lacquer coat to seal it in, which prevents him from touching it further. But just prior to the lacquer, he paints a few swirls of gold leaf, an homage to Gustav Klimt. Prices range from $3,000 to $10,000 and most of his work is sold via his Instagram, @Bacchusbysilva.

The final ritual before the lacquer, which did begin during the pandemic, is the inclusion of poker or tarot cards. Without looking at the decks, he selects several cards and adds them to the painting. These cards speak to his personal philosophy on life.

“I think that we we’re all given a deck of cards when we come into this life, and those are meant to be played during different stages of our lives,” he explains. “For example, when you are a teenager, there are certain cards you can play. But as you become older, you have different cards in front of you, and you cannot play the same cards you played as a teen. One day, you’re going to look at your deck of cards and see that the stack is getting lower and lower.”

“There will be time, and this is my own theory, that I will be on my deathbed, and I’m going to look at my last two or three cards. And I’m going to play them right.”

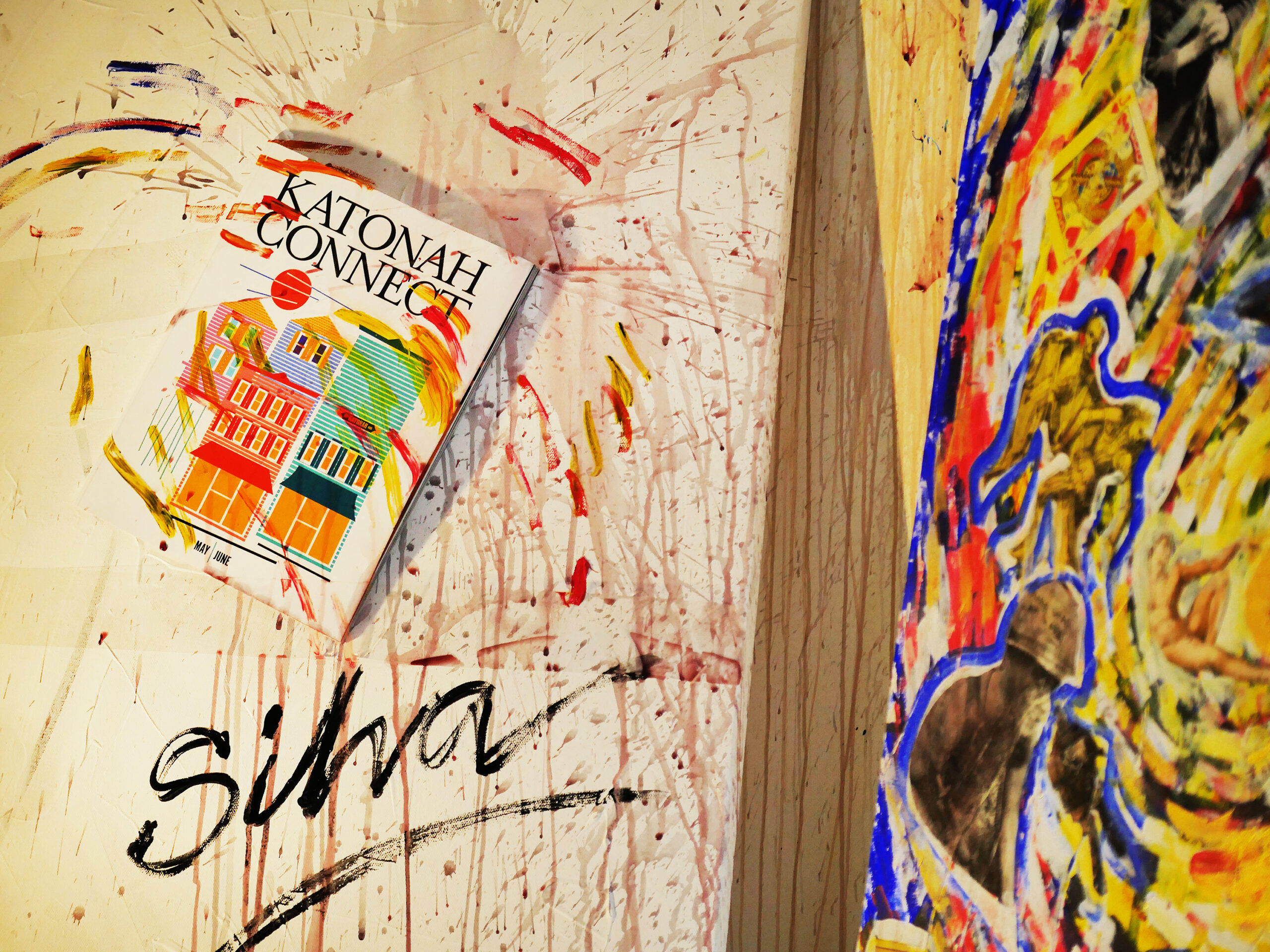

This article was published in the November/December 2022 print edition of Katonah Connect.

Gia Miller is an award-winning journalist and the editor-in-chief/co-publisher of Connect to Northern Westchester. She has a magazine journalism degree (yes, that's a real thing) from the University of Georgia and has written for countless national publications, ranging from SELF to The Washington Post. Gia desperately wishes schools still taught grammar. Also, she wants everyone to know they can delete the word "that" from about 90% of their sentences, and there's no such thing as "first annual." When she's not running her media empire, Gia enjoys spending quality time with friends and family, laughing at her crazy dog and listening to a good podcast. She thanks multiple alarms, fermented grapes and her amazing husband for helping her get through each day. Her love languages are food and humor.